To

A new study led by Harvard University reveals the critical role the thymus organ plays in maintaining immune health and preventing cancer in adults. The study found that those who had a thymectomy had a significantly higher risk of dying from a variety of causes, including a double cancer risk.

Studies have shown that certain organs play an important role in immune health, especially in cancer prevention.

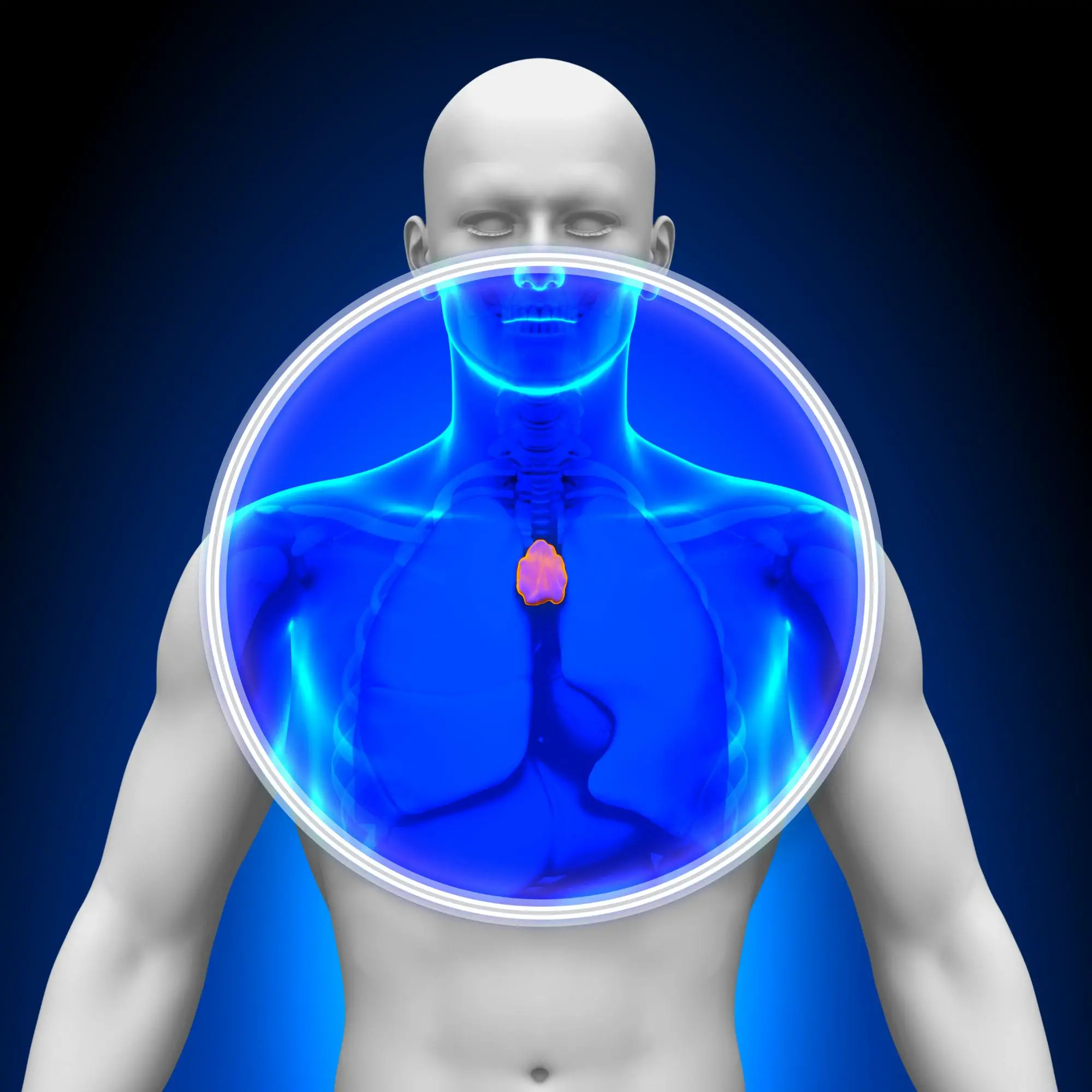

Many people cannot tell where their thymus is or what it does, and even doctors have long thought that the adult thymus is expendable. But a recent study led by Harvard University shows that this walnut-sized organ located in the chest is essential for maintaining immune health as we age, especially in preventing cancer. is proposed. Especially in cancer prevention.

In this study, data from individuals who underwent thymectomy were evaluated and compared with those who did not undergo thymectomy. They found that those who had the thymectomy had an almost three-fold higher risk of dying from a variety of causes, including cancer and autoimmune diseases. Specifically, her risk of cancer doubled and her risk of autoimmune disease increased slightly.

“The magnitude of the risk was something we never expected,” said Gerald and Darlene Jordan, professors of medicine, Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, published in 2006. said David Skaden, who led Research Link. New England Journal of Medicine This is a collaborative study with researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The main reason why the thymus affects overall health appears to be a means of preventing the development of cancer.”

According to Skadden, the thymus is the organ that ages the fastest. In early childhood, he is most active in producing a large amount of T cells, but around puberty, he begins to atrophy and become adipose tissue. For decades, scientists therefore assumed that it served only a limited purpose in adulthood. It is usually removed during other cardiothoracic surgeries because of problems with the organ itself, such as thymic carcinoma, or because it is located in front of the heart and often interferes with the surgeon.

In recent years, however, scientists have begun to suspect that the thymus may play a major role in our age-related health by continuing to produce T cells that contribute to the diversity of T cell populations throughout the body. I was there.

Kameron Kueschesh (left to right), David Sykes, David Skaden and Karin Gustafsson working in the MGH lab.Credit: Kris Snibbe/Staff Photographer, Harvard University

“This study shows how important the thymus is to the health of adults,” said Skadden.

Lead author Kameron Kueschesh was intrigued by an unanswered question about the adult thymus during a sophomore course in neurology at Harvard Medical School. He learned that surgical removal of the thymus was recommended for patients with myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disease, as a way to stop the immune destruction of nerve endings by T cells. “Nevertheless, clinical instruction in the surgical ward has shown that the thymus is thought to be a hallmark of adulthood,” Kueschesh said. “These two philosophies seemed to him diametrically opposed, and he wanted to learn more.”

For this study, Dr. Kueschesh collected data from 1,146 adult patients who underwent thymectomy and demographically matched control patients who underwent similar surgery but retained their thymus. Kueschesh and Skadden collaborated with Brody Foy, a biostatistician who helped direct the team’s statistical study on the epidemiology of thymectomized patients, and Karin Gustafson, an expert in T-cell biology. did MGH’s David Sykes helped the team facilitate blood collection for patients.

In an analysis of all patients with at least 5 years of follow-up, mortality in the thymectomy group was higher than in the general U.S. population (9% vs. 5.2%; cancer deaths: 2.3%) vs. 1.5%. .

In the subgroup of patients whose T-cell production was measured, de novo production of T-cells, including both helper and cytotoxic T-cells, was reduced in thymectomized patients. Those patients also had elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, small signaling proteins associated with autoimmunity and cancer, in their blood.

“The number of deaths and cancers in patients undergoing thymectomy was the biggest surprise to me,” said Kushesh, now a medical resident at MGH. “The more we dig, the more we learn. The results suggest that the absence of the thymus appears to disrupt a fundamental aspect of immune function.”

This analysis was facilitated by recent advances in rapid gene sequencing of the T-cell receptor (TCR). The technique, called TCR sequencing, has enough resolution for the scientist to not only distinguish between different types of her T cells, but also to measure the diversity of T cells in the population as a whole.

Reference: “Health Effects of Thymus Removal in Adults,” Kameron A. Kooshesh, Brody H. Foy, David B. Sykes, Karin Gustafsson, David T. Scadden, 3 August 2023, Available here. New England Journal of Medicine.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJ Moa2302892

This study was supported by the Tracy & Craig A. Hough Harvard Stem Cell Institute Research Support Fund, the Gerald and Darlene Jordan Professor of Medicine, National Institutes of HealthAmerican Society of Hematology, Swedish Research Council, John S. McDougal Jr. and Olive R. McDougal Foundation.