Across the United States, about three-quarters of people enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan (a form of private insurance that follows Medicare rules) receive a free gym membership. why is this?

The answer, according to research, is that it will improve the customer base of insurers. The promise of free workout time won’t lure existing customers off the couch to the gym, but it will attract new customers who are healthier than average. When customers are healthy, insurers pay less and make more profits.

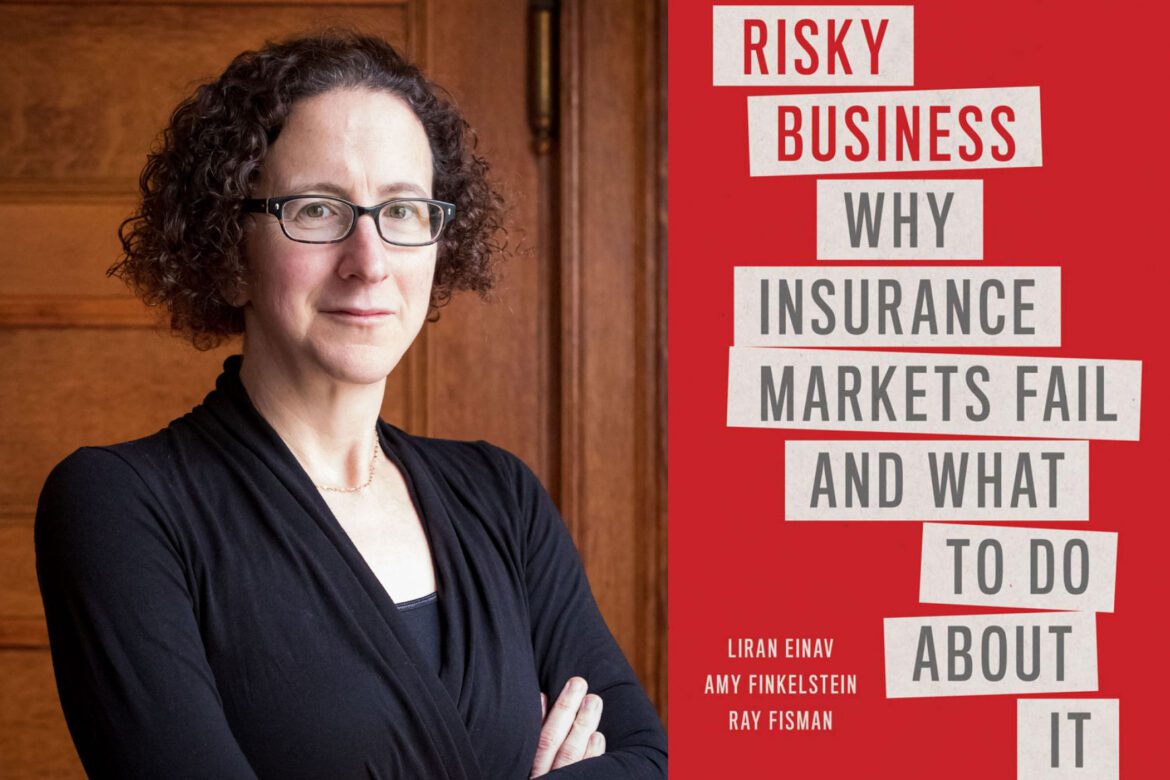

“What the data tells us is that these programs are actually attracting healthy people,” says MIT economist and insurance scholar Amy Finkelstein. It’s very difficult for a company to observe potential customers, and if you want a customer who is in better shape than you can observe, who wants to go to the gym, finds it attractive? Finding people who are there is a very good way to identify those new customers.”

The entire insurance industry then revolves around the struggle to attract what kind of customers. People want insurance just in case something happens. But insurers want customers who need few surgeries, car repairs, or whose homes won’t slide into the ocean. This makes insurance a distinctive industry.

After all, supermarket chains and car dealerships aren’t overly concerned about who buys their products, as long as the sales are good enough. But for insurers, solving this problem right will keep them in business, but getting it wrong will destroy the company and the market.From an insurer’s perspective, attracting too many needy customers is a problem of ‘adverse selection’ in business

“Insurers are very concerned about which customers buy their products,” says Finkelstein. “Because an insurance company’s profit depends not only on how much it sells, but on who it sells to.”

Finkelstein, a John and Jenny S. Macdonald professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, co-authored a new book on the subject, Risky Business: Why the Insurance Market Fails and What to Do About It. Published today by Yale University. press. It was written with Liran Einav, an economics professor at Stanford University, and Ray Fisman, an economics professor at Boston University.

Adverse selection problems everywhere you look

Finkelstein is a leading authority on health insurance and has collaborated with Einav on research papers on this topic. However, “risky business” includes many different types of insurance, such as life insurance, auto, and dental. In all these areas, companies go to great lengths to avoid adverse selection. This explains many of insurance’s frustrating or quirky features.

For example, why are there only a few weeks of “open registration” for health insurance companies a year? Or if you have life insurance, why is there a waiting period before the policy goes into effect? Why would a car insurance company care about your GPA?

In either case, the answer comes with a choice. There is an open coverage period so people don’t have to wait to have a specific medical diagnosis before choosing insurance. When it comes to dental insurance, studies show that people are very aware of their dental needs and are willing to wait until they need more dental care before upgrading their plans.

This may seem exactly how insurance works for consumers. Sign up for what you need and get a refund. But the purpose of insurance as a system is to provide a buffer against the vagaries of fate. Waiting to join until things get worse can create a vicious cycle. When enough consumers need help and payments increase, premiums can rise and become unaffordable. In the meantime, companies and industry sectors may collapse.

“One of the biggest problems with adverse selection is that the market can disappear entirely,” says Finkelstein.

This is also why there is a waiting period for insurance. Often for life insurance he is 2 years and for car insurance he is 1 week. As the book details, Finkelstein’s husband, his economist at MIT, Ben Olken, was in graduate school when his car broke down. Waiting on the shoulder of the road for his AAA to arrive, he called to upgrade his car insurance. To my delight, Olken was told that coverage could be expanded. Unfortunately, he was then informed that the new policy would not start for his week. Blame it on adverse selection.

“We try to show that there is a common theme behind many things in the world,” says Finkelstein.

In fact, auto insurance companies want to know the educational background of prospective customers. Whatever the reason, people who are more successful in school charge less for their car insurance. From time to time, companies come up with new ways, such as gym membership offers, to build a base of infrequent consumers who need insurance.

It has taken insurers a while to get to this stage, as the business at risk shows. In the late 17th century, Edmund Halley, better known for his eponymous comet, used German census records to price annuities, a type of insurance that guaranteed annual payments until he died. developed the first systematic method to Just because Halley did not consider adverse selection, it was not a viable system.

secret knowledge

We know everything insurers know about people in the age of big data, but the industry still doesn’t know it all. Studies show that people with life insurance are more likely to die younger. However, it is unclear why, based on available health indicators.

“We still don’t quite understand what people know, but life insurance companies don’t understand,” says Finkelstein.

As the authors detail in their book, adverse selection puts policy makers in a bind. It may seem fair and just to make health insurance the same price for everyone, even those with observable problems. The numbers may not add up for insurers, as evidenced by the collapse of state-backed health insurance exchanges in New Jersey and New York that required

“In some ways it was fairer, in that no one was treated differently and everyone suffered from a lack of insurance,” said Finkelstein. “We need to understand these trade-offs and make more informed decisions.”

The Affordable Care Act famously addressed adverse selection by requiring everyone, including healthy people, to have health insurance and providing subsidies to those who had it. This approach has been the subject of much debate, but acknowledges the central tensions of insurance.

“Sometimes getting the policy right doesn’t mean making the world perfect, but deciding how to balance different kinds of issues,” says Finkelstein.

Experts praise its approach to describing “risky business” and its insurance market. Nobel Prize-winning economist Dr. George Akerlov ’66 said:risky business’ Not only is it super fun. They also subtly reveal the foundations of many economics. ”

Finkelstein hopes the book will be of interest to a wide range of readers. Readers, whether satisfied with the content or dissatisfied with insurance, will at least be satisfied with understanding why the industry as a whole is in its current form and practice.

“We see our role as helping people better understand the world around them,” she says.