Three days into the opening of the World Health Assembly (WHA), the health emergency sparked by Russia’s 15-month-long invasion of Ukraine is at the center of discussion by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) highest decision-making body for the second year in a row. seems to be a point of contention. .

Since the beginning of this month, more than 140 Russian missiles and drones have rained down on Ukraine’s energy, civilian and medical infrastructure. The effects of the onslaught continue to affect millions of civilians, displacing nearly 10 million people since the war began, jeopardizing access to physical and mental health care.

Supply chains for essential medicines have been disrupted, hospitals have been destroyed and medical facilities that remain operational have been forced to fight to keep the lights on amid periodic blackouts due to attacks on Ukraine’s power grid. ing. 1 in 5 ambulances in the Ukrainian medical fleet is damaged or destroyed.

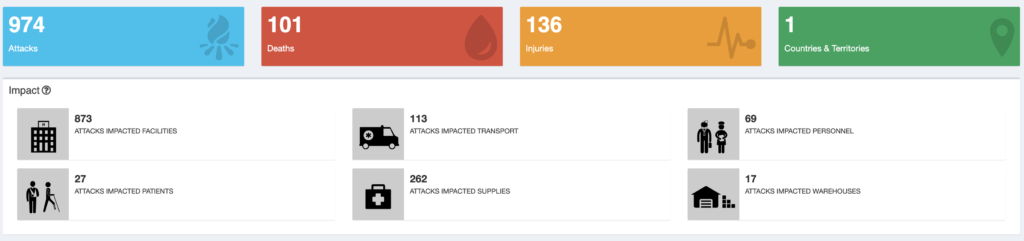

The overwhelming focus of the Geneva delegation on the health crisis in Ukraine is well-founded. Ukraine told a WHA delegation on Tuesday that more than 1,256 health facilities had been damaged, with a further 177 reduced to rubble. The World Health Organization has independently confirmed 974 attacks on health facilities and the deaths of more than 100 health workers since the war began.

Other Humanitarian Emergencies – Is There Enough Time to Discuss?

But in the midst of a spate of humanitarian crises and a resurgence of familiar fighting that was litigated at the WHA last year, the question of whether there will be enough time left to discuss the plight of millions of civilians outside Ukraine remains an open question. Remains resolved.

The World Health Organization now counts the 13 ongoing crises as “Grade 3” emergencies, the highest level of internal threat to the United Nations Health Organization. These include the lingering drought in the Horn of Africa, the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan, and the ongoing conflicts in Yemen, Syria and Ethiopia. A deadly civil war, characterized by regular attacks on hospitals and civilians, has also erupted in Sudan, forcing hundreds of thousands to flee the country and threatening stability in the wider region.

Civilian casualties in armed conflicts have also increased by 53% year-on-year since 2022, according to a report released by the Swiss presidency of the UN Security Council on Tuesday, with an over-focus on Ukraine leading to a loss of civilians. There is growing concern that the damage caused by I expressed the conflict on the roadside. The report added that more than 90% of the deaths from explosives detonating in populated areas were civilians.

The draft resolution submitted by Ukraine and its allies on Monday is nearly identical to the resolution passed by the WHA in 2022, and has the same title, but states that Ukraine’s health crisis “results from Russian aggression.” ing.

Russia again responded by proposing its own draft resolution calling on states to “restrain themselves from the politicization of global health cooperation” and “respect their obligations under international and humanitarian law.”

Syria, a co-sponsor of the resolution, called on WHA representatives to support Russia’s draft to “avoid escalating crises” and “help further stabilize Ukraine and its neighbors.”

Currently, only North Korea, Nicaragua and Belarus among other WHO member states have expressed support for the Russian resolution.

Ukraine says vote to show WHA will not tolerate attacks on medical infrastructure

On Tuesday, the Ukrainian delegation called on the WHO’s 194 member states to support a resolution condemning Russia’s “aggression”. He called on countries to reject Russia’s opposing resolution, saying the resolution was based on a “distorted alternate reality.”

“The Russian document is nothing more than a desperate attempt to put the aggressor on a par with the victim and avoid responsibility for the attack on the Ukrainian health system,” the delegation said. “[Voting down the resolution] Creating a major health emergency and destroying a large medical structure would send a clear signal that it will not be tolerated by this Congress. ”

Meanwhile, Russian diplomats have protested statements condemning actions in Ukraine by Poland and other Ukrainian allies, saying Russian representatives “have nothing to do with the WHO’s mandate”.

Russian intervention has so far been rejected by WHA President Dr Christopher Fern and other committee chairs, citing the scale of the health crisis caused by the war.

And the language is getting hotter and hotter.

“Russia has no respect for human life,” said the Estonian representative. “Suspend the Russian Federation from decision-making” [of WHO] Until full respect for international law and human rights is restored. ”

Russia distributes documents accusing Ukraine of attacking its health system

In the first year of the Russian invasion, an average of two attacks on medical facilities were reported each day. These include strikes on hospitals, shooting of ambulances, torture of health care workers and looting of medical facilities.

Yet Russia has not stopped attempting a diplomatic counterattack. To garner support for the draft resolution, Russian diplomats circulated pamphlets at the WHA accusing Ukraine of attacking its own hospitals and medical facilities.

The UK representative referred to the move during heated debate on Tuesday afternoon, comparing it to “theater of the absurd”.

“We are aware that, like last year, Russia circulated pamphlets to other delegations claiming that Ukraine was attacking their health system,” British diplomats told parliament. “We are confident that our representatives here today will not be fooled by such disinformation.”

Russia has not openly expressed such denunciations in its statements at the WHA. However, the draft resolution states that the WHO Surveillance System for Medical Attacks (SSA), the United Nations Health Organization’s database that records attacks on health facilities and staff, does not accurately reflect “all incidents involving attacks on health.” It expresses “grave concerns” about it. nursing home. ”

It also called on the WHO to improve its collection of “data on attacks against medical facilities, medical personnel, medical transports and patients”, which it said had carried out nearly 1,000 attacks on healthcare in Ukraine. It is a strange request for the condemned country.

It’s not the first attack on a medical facility in Ukraine

There have also been attacks on hospitals, medical workers and civilians by Russian forces in the Syrian intervention. well documented By rights groups. Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria and the main co-sponsor of the Russian resolution, said: repetition It used chemical weapons to attack civilians to stay in power.

The Russian resolution also calls on states to “refrain from deliberately placing military objects and equipment” near civilians or civilian infrastructure, or in “populated areas.”

The language of the Russian text seems to reflect some research findings. report Amnesty International, in a statement in August, accused the Ukrainian military of repeatedly “endangering civilians” by stationing soldiers in nearby areas and conducting operations out of populated areas.

Russian officials claimed the report vindicated Russia’s actions in Ukraine. Russia’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Vasily Nebenzia, said the report proved that Russia was not using “a tactic used by the Ukrainian military of using civilian material as a military cover”. .

An independent review of the report later found that Amnesty International’s allegations that Ukraine violated international law were “not sufficiently substantiated.”

The review also said some of the language used by Amnesty International was “legally questionable”, notably that “the Ukrainian military is primarily or equally responsible for the deaths of civilians” from the Russian attack. It said it was “legally questionable” about the implications of the report.

Image credit: Matteo Minasi/Unocha, Christian Traibert.

Fighting the infodemic in health information and supporting health policy reporting from the global South. Our growing network of journalists in Africa, Asia, Geneva and New York connects the dots between local realities and big global debates with evidence-based, open-access news and analysis. To donate as an individual or organization, click here on PayPal.