Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about interesting discoveries, scientific advances, and more.

CNN

—

Finding a cure for cancer is a driving force for many aspiring doctors. Few people come close to pursuing that goal. Among them is Dr. Katherine Wu, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. She had been suffering from cancer since she was in second grade. Her teacher asked her and her classmates what she wanted to be when she grew up.

“At the time, there was a lot of press coverage about my battle with cancer,” she said. “I think I drew a picture of a cloud, maybe a rainbow, and it looked like I was creating a cure for cancer or something.”

That childhood doodle was prescient. Wu’s research laid the scientific foundation for the development of cancer vaccines tailored to the genetic makeup of an individual’s tumor. It’s an increasingly promising strategy for some hard-to-treat cancers, such as melanoma and pancreatic cancer, and could eventually treat around 200 cancers, according to results from early-stage trials. It has the potential to be widely applied to many applications.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which selects Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, awarded Wu the award last week. sjöberg award In honor of his “definitive contribution” to cancer research.

Cancer treatment “has advanced over the years, but there are still many unmet medical (needs).” There are many forms of cancer,” said Urban Ländahl, professor of genetics at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet and executive director of the committee that awarded the award.

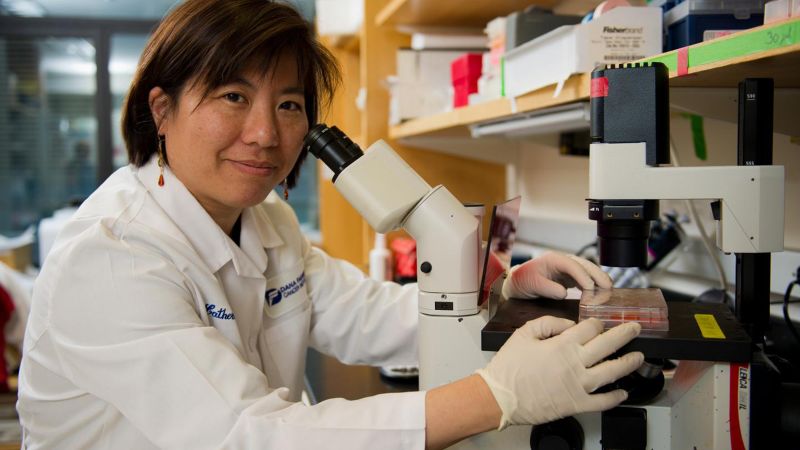

Sam Ogden

Dr. Katherine Wu and her close collaborator, Dr. Patrick Ott, have been working to develop a vaccine to treat melanoma.

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy, the most common treatments for cancer, are like sledgehammers that attack all cells and often damage healthy tissue. Since the 1950s, cancer researchers have been looking for ways to boost the body’s immune system, which succumbs to the body’s natural attempts to fight cancer and attacks tumor cells.

Progress on this front was modest until around 2011, when a class of drugs called checkpoint inhibitors emerged that boosted the antitumor activity of T cells, a key part of the immune system. This work led to 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine awarded to Tasuku Honjo and James Allisonthe latter is the winner of the 2017 Sjöberg Prize.

These drugs have helped some cancer patients who were given only months to live survive for decades, but they do not work for all cancer patients, and researchers are We continue to explore ways to strengthen the body’s immune system.

Wu became interested in the power of the immune system after witnessing a bone marrow transplant as a medical resident and seeing how the blood and immune system are rebooted to fight cancer. Ta.

“I had a really formative academic experience that made me very interested in the power of immunology,” she said. “I had people in front of me who were being cured of leukemia by activating their immune response.”

Christine Olson/AFP/Getty Images

Japanese scientist Tasuku Honjo (left) and American scientist James P. Allison, winners of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine, have laid the foundation for a new class of cancer drugs.

Wu’s research focused on small mutations in cancer tumor cells. These mutations, which occur as tumors grow, produce slightly different proteins than healthy cells. The altered proteins produce what are called tumor neoantigens, which are recognized as foreign by the immune system’s T cells and are vulnerable to attack.

Rendahl said there could be thousands of neoantigen candidates, so Professor Wu used “powerful laboratory work” to identify neoantigens present on the cell surface and identify them as potential targets for vaccines. He said that.

“If the immune system is to have a chance of attacking the tumor, this difference has to appear on the surface of the tumor cells. Otherwise, there is no point at all,” Rendahl added.

The idea of a cancer vaccine has been around for decades. The widely used HPV vaccine targets the virus that is associated with an increased risk of cervical, mouth, anal, and penile cancer. However, cancer vaccines often fail to live up to their promise. The main reason is that suitable targets have not been found.

Hans-Gustav Ljungren, Professor of Immunology at Karolinska Institutet, said: “The ability to identify neo-specific tumor antigens is a major area of cancer research, as it offers the possibility of generating tumor-specific cancer vaccines. It has actually developed.” In a video shared by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. “This is an amazing discovery.”

By sequencing the DNA of healthy and cancer cells, Dr. Wu and her team identified tumor neoantigens that are unique to cancer patients. Synthetic copies of these unique neoantigens could potentially be used as personalized vaccines to activate the immune system and target cancer cells. Wu and her team wanted to test the technology on patients with advanced melanoma in a clinical trial.

For the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates clinical trials, the idea that every patient in a trial could receive an individual vaccine was initially difficult to grasp as a whole, Wu said. The FDA typically requires vaccines to be tested on animals first.

Wu and her team argued: It was the first of its kind and people came from different offices. Our discussion was, “This is personal, and everything we do with animals doesn’t really match up with humans. So why go down that path?”

Matt Stone/Media News Group/Boston Herald/Getty Images

Several cancer vaccine trials are currently underway, but the scale is small. Further research is needed before these become viable treatment options for many cancer patients.

Once approved by the FDA, the team vaccinated six patients with advanced melanoma with a seven-dose course of patient-specific neoantigen vaccine. The breakthrough results are 2017 article in Nature magazine. In some patients, this treatment activates cells of the immune system to target tumor cells. result, Other papers have also been published, That same year, the founders of mRNA vaccine company BioNTech provided “proof of principle” that vaccines could target specific tumors in individuals, Rendahl said.

Follow-up by Wu’s team Four years after the vaccination announced in 2021, the immune response was shown to be effective in suppressing cancer cells.

“We are grateful to all the patients who participated in our trials because they are… active partners,” Wu said. “It’s hard enough just to get treatment, but then to be able to receive treatments of unknown efficacy and be willing to accept all the additional fees that are required to do this kind of research is hard enough.” There are more tests, more blood draws, more biopsies.”

Since then, Wu’s team, other groups of medical researchers, and pharmaceutical companies including Merck, Moderna, and BioNTech have carried out further research. developed this field Vaccine trials are underway. pancreas treatment and lung cancer So is melanoma.

All ongoing trials are small and involve a small number of patients, usually with terminal illnesses and a high tolerance for safety risks. Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to show that this type of cancer vaccine is effective.

“The numbers are low for obvious reasons,” Rendahl said. “The data looks promising, but of course it’s still early days.”

Scientists are also figuring out the most effective way to form vaccines. Wu’s group and others have used vaccines made from peptides or a series of proteins. Moderna and BioNTech are using mRNA, which the companies pioneered in developing a vaccine against Covid-19, to deliver a set of instructions to cells to make related proteins.

“My belief is that there are many roads to Rome. I believe there are many different delivery methods, and each delivery approach can be optimized with different bells and whistles,” Wu said. states. “It takes investment to make that delivery approach work to its full potential. And now, with the pandemic, there is a huge demand for mRNA.”

Cancer vaccines have shown the most promise in “hot tumors,” a colloquial term used by oncologists that mutate rapidly, such as melanoma, which was Wu’s initial focus. It is unclear whether it is effective against more inactive “cold tumors” such as breast cancer.

“It’s easier if there are more mutations occurring naturally within the tumor, because we have better information on potential small molecules that we can choose from to make a vaccine,” Rendahl said. said.

Another challenge is how to manufacture these vaccines in a more cost-effective and time-sensitive manner so that they can reach large numbers of cancer patients, Wu said. . Currently, manufacturing an individual vaccine at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars can take weeks, if not months. An active research avenue is the development of vaccines that target neoantigens common to patients with the same type of cancer, raising hopes for “off-the-shelf” vaccines that can be used by many people without lengthy individualization processes. .

Another question is whether vaccines can be combined with other treatments to make them more effective, and if so, which treatments.

Test results The vaccine developed by Merck and Moderna, announced late last year, Administered to patients with advanced melanoma In conjunction with a type of immunotherapy called Keytruda, The companies said the checkpoint inhibitor-based drug had a lower risk of recurrence or death than patients who received the drug alone.

It is also unclear at what point in the treatment cycle a vaccine would be most useful: treating cancer detected early, helping patients with advanced disease, or ensuring that patients remain cancer-free. Most of the ongoing trials are targeting late-stage cancer patients or those in remission, but Professor Wu said he believed the vaccine could be more effective in early-stage cancers. Ta.

Despite so many unknowns, for some of those involved in these early cancer vaccine trials, the results were life-changing

“I’m so grateful to have been given the shot,” said Barbara Brigham, who received BioNTech’s personalized vaccine for pancreatic cancer that is being tested. he told CNN last year.. She was able to watch her oldest grandchild graduate from college. She never thought she would live to see that moment. “The opportunity and timing were perfect,” she said. “It helped me, and I hope it helps someone else.”

CNN’s Brenda Goodman contributed to this report.