My brother has an unusual medical condition. He was born with many disabilities and survived meningitis with severe brain damage. I became a doctor because of him, and in medical school I clarified his illness in a lecture. I learned about his disability in anatomy by examining the joints and organs of the corpse. In neurology and pulmonology, he learned about his breathing problems, and in the cardiac ICU, he learned how to put it all together to understand why his heart kept failing him.

On Saturday we spent the day in silence, improving our skills and speaking only sign language to communicate with him. I wanted to know what my brother was thinking about every day in his life. How could we have existed, living parallel but radically different lives, simply as a result of the body? It is something that you will eventually have to adapt to.

The truth is, I’m obsessed with the body, and it’s so mysterious and so simple all at once. As a Muslim, I grew up with the idea that the human form is made out of clay, dust, and dirt. It is somehow demeaned by its sheer worldliness.

When you open up the body, it’s pretty much the same, nicely organized and organized in a predictable way. But there are great differences between us in our humanity, our appearance, our medical conditions. For example, a tumor can change our sanctity of similarity.

My brother’s body reflects the rare genetic syndrome he was born with: fused cervical spine, solitary kidney, short stature, flat back of head, missing cochlea. His body, though non-traditional in its composition, is functional. Medicine, in all its physiological complexity, is largely formulaic, thus leaving his medical anomalies resolvable. But medicine is not benign, and despite our understanding of what constitutes a human being, doctors make mistakes. All interventions are not without results, but it’s hard to have empathy. How much have we changed his life and mine?

The first time I made an incision during surgery was when I was a third year medical student undergoing a kidney transplant. I carefully cut away the skin and opened the abdomen to the smooth peritoneum so that the saran encased the internal organs. I wanted to touch each and every one of them.

Over the past year, my brother’s lone kidney has failed. His name is on the country’s transplant list. For years, Muslim theologians have debated the moral implications of organ donation. They wondered whether removing an organ could be considered sacrilege of the body so that the soul could ascend to heaven. Some even consider it an eternal handout. The act of permanently changing one’s physical self, once discouraged, is now made holy by saving another.

I want to give my brother one of my kidneys. Her mother is against the idea. She has many crises mentally, logically and emotionally. Her own sister had her kidney transplant twice in her lifetime as a result of a long and complicated illness. she is afraid I think she understands. But part of me knows what she doesn’t know, the intricacies of surgery: retrieving a kidney from one body, how the new kidney fits into the recipient’s pelvis, and how the blood re-entered. Flash that can be obtained at times. The accuracy of the calculated body is reassuring even if it fails.

I often think about my body and the stories it tells. Like my brother, my body is syndromic. The word “syndrome” itself refers to a constellation of features that appear together and are assigned to a particular disorder when correlated with each other. Mine is also rare, but relatively benign — a syndrome of limited lateral mobility in the left eye due to a failure of neuronal migration. The syndrome itself has been studied and is rarely inherited. It is believed to be associated with certain genetic mutations. By the way, some of my brothers and sisters may have my brothers and sisters. did. A genetic correlation between our syndromes has not been established. In fact, both of these syndromes often occur as spontaneous mutations and are rarely inherited.

It seems like a strange fate that two of my parents’ four children have a rare genetic syndrome. But lightning strikes him twice, much more than we know. Perhaps it’s just chance that our genome deviates from the traditional genome. More than anything, it feels like our destinies are bound together so that one piece of her genetic code can change our destinies and allow us to live each other’s lives.

There are six antigens known to be most important for tissue typing for organ transplantation. We inherit three from each of our parents. A perfect match of her six antigens between two people is rare, unless they are siblings or identical twins. The body makes antibodies against other people’s antigens. When it is strong, it leads to rejection of the transplanted organ. The better the match, the less likely it will be rejected.

On average, a kidney transplant lasts about 10 years, sometimes longer, sometimes less. If a kidney is not available, the person remains on the transplant list while undergoing dialysis, and all blood is extracted and purified through a machine 100 times her size in that small organ, the kidney. . Recently, the Supreme Court ruled that insurance companies can limit a patient’s access to dialysis sessions despite a doctor’s recommendation, leaving the patient with the aftereffects of organ deterioration.

When the kidneys fail, there are distinct metabolic abnormalities. Electrolyte imbalances lead to acidosis and the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products. The resulting uremia eventually causes many end-organ symptoms, including central nervous system decline. One of my professors in medical school explained that dying of end-stage renal disease is the same as falling asleep.

In Islamic theology, the soul (rūḥ) is separated from the ego (nafs). The ego itself is earthly in nature and related to the body. The ego is divided into his three parts defined by desires. The first is what is low and wrong with the base. Last for holy, righteous and good. The part of the ego that lives in between is the part that wants both and lives condemning the guilty self. Existence itself becomes synonymous with Naf’s challenge. A firm grasp of one’s desires is the attainment of tranquility.

nafs is always at odds with itself. Some days I understand my desire to donate a kidney as a way to reconcile the threads of the genetic code that separate my life as a doctor and my brother’s life as a patient. At the same time, I understand that I accept my mother’s fear as a reflection of myself. No matter how knowledgeable I am, I know doctors are prone to mistakes. I am also one of them. My ego remains imbalanced in one direction or another on any given day. My arrogance meets fear and devotion. Naf of love for God and Naf immersed in this physical world: I wonder which reflects the other.

During surgery last week, I put my finger on a woman’s aorta. Her heart pounded under my fingers, her entire blood supply passing while I removed her tumor. She was under anesthesia, and somewhere between the worlds of the living and the dead, my hand was placed inside her body – a fact she would never know or remember.

Despite my understanding of the body, medicine and science do not explain the abstract part of our self-defining existence, the essence of being alive. In fact, we can dissect every part of the human body and explain its mechanism down to the core. Spiritually, we each have different beliefs about how we came into being in the universe. In truth, I don’t see that it matters whether you know one or the other. After all, we live our best until we become obsolete.

I have thought a lot about the life my brother has lived and what the end might look like. As a doctor, I know that I would rather die at home with the people I love and with the least amount of medical intervention possible. I don’t know. That thought hits me.

Yet Islam gives us eternal life beyond the limits of this body. I’m human, so my ego questions my faith and the nuff crumbles in different shades. i have to believe it. In that realm, the brother’s spirit can exist without end. In that world, he is free from the bodily afflictions that frustrate him. We can meet as equals in a metaphysical way, without the dynamics of dependence between us.

It’s a small thing, but the idea of donating my organs is like a tangible expression of my love for my brother, who has been with me all my life, and my mother, our first physical home. A part of me, at least on this earth, will always be with him. Does that make it more or less sacred?

I recently called my mom and asked her if she remembered that night in New York many years ago. When the firefighter came down the stairs after work, I returned to the room I shared with his sister, flipped the light switch, and stared at my street neighbors through the windows. opened. The hum of his ventilator echoed through the night. someone waved. I waved from my window perch as our house glowed in the darkness.

¤

¤

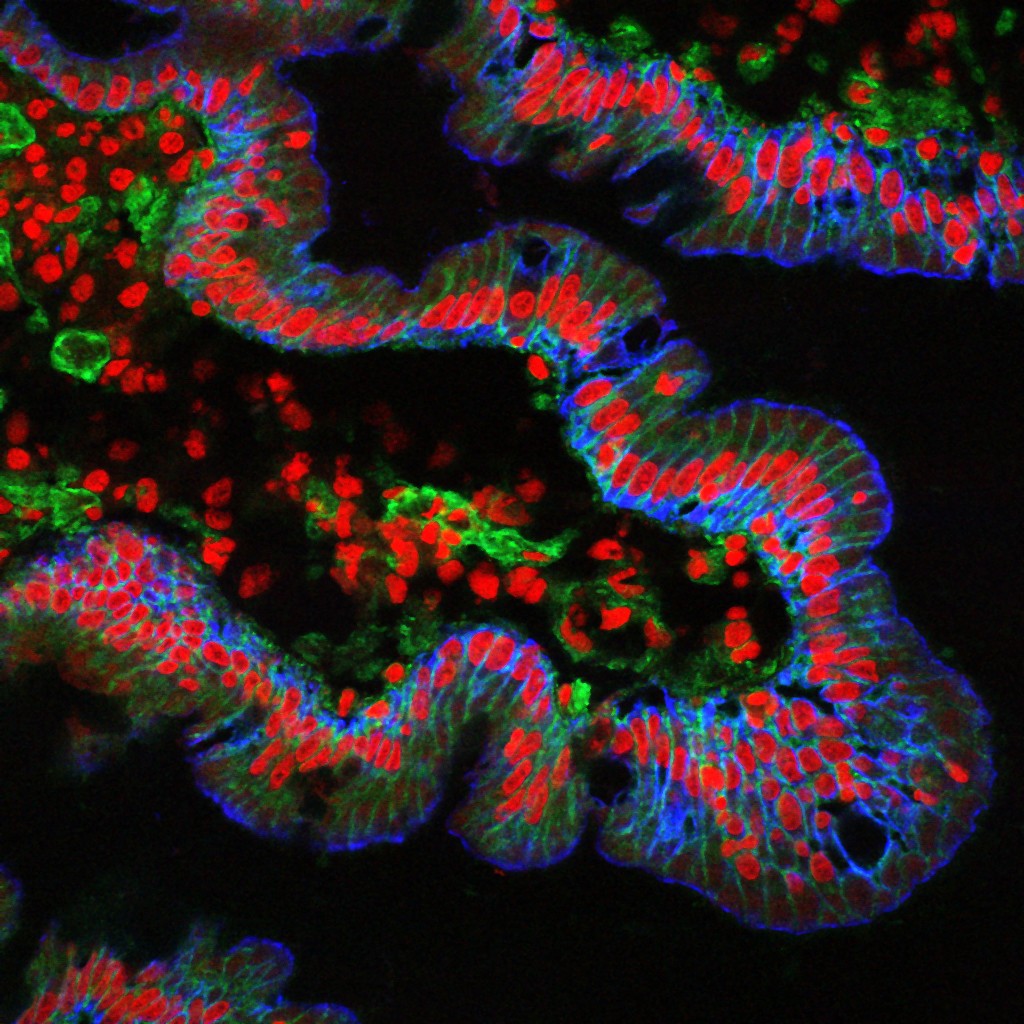

Featured Image: S. Shuler. villi from the small intestine. welcome collection. wellcomecollection.org, CC BY 4.0. Accessed 21 October 2022.