In mice, vaccination prevents toxin-related intestinal damage by diarrhea-causing bacteria

Alaura Sheikh

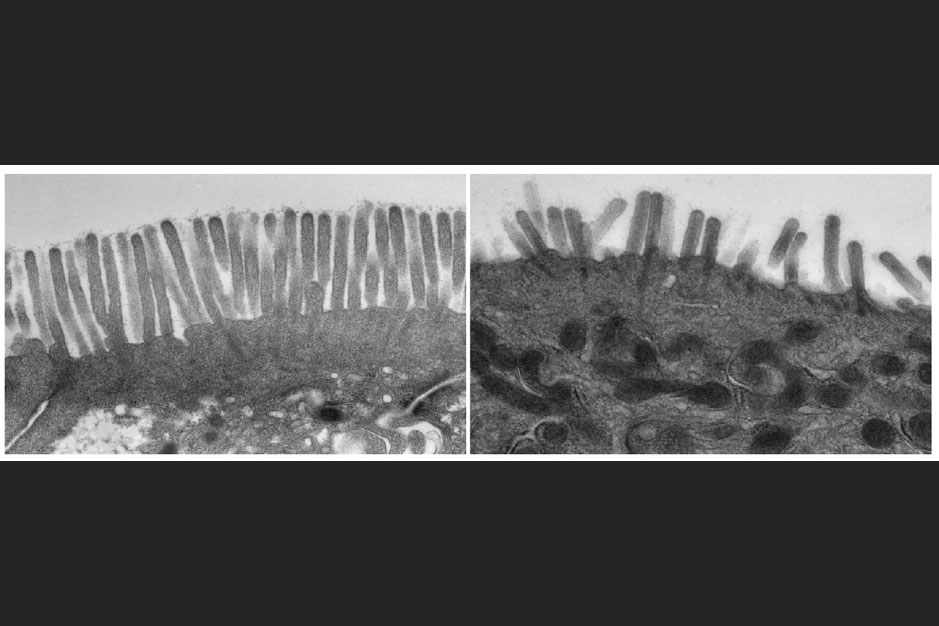

A healthy intestinal lining has dense projections called microvilli that absorb nutrients (left), but exposure to bacterial toxins damages the microvilli (right), impairing nutrient absorption. Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that vaccinating mice against the toxin can prevent intestinal damage.

Diarrhea is no longer the killer it was in the mid-20th century, when an estimated 4.5 million children under the age of five died from it each year. Lifesaving oral rehydration therapy has turned the tide, but it does not prevent infections. Millions of children in low- and middle-income countries continue to endure recurring diarrhoea, weakening their bodies, making them vulnerable to malnutrition and stunting, and diminishing their ability to fight off a range of infectious diseases. .

Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in a study of human cells and mice, have determined how the causes of certain types of diarrhea vary. Escherichia coli (Escherichia coli) bacteria damage the gut, causing malnutrition and stunting.And they said that vaccination against toxins produced by Escherichia coli Protects infant mice from intestinal damage.

The findings suggest that a vaccine against this species is Escherichia coli We can help drive global efforts to ensure that every child is not just turning 5, but thriving. This study is available online at Nature Communications.

“Ideally, we would have a vaccine that would prevent acute diarrhea, which still kills half a million children a year, and protect against long-term effects such as malnutrition, which is probably a big part of the problem today. We want to put it in,” said the senior author. James M. Fleckenstein, MD, Professor of Medicine and Molecular Microbiology. “When children are malnourished, they are at greater risk of dying from any cause. The World Health Organization is in the process of determining how to prioritize vaccines for children in low- and middle-income countries, and these data will to vaccinate us Escherichia coli Diarrhea can be very beneficial in areas afflicted with this.

Fleckenstein is doing a kind of research Escherichia coli known as enterotoxigenic Escherichia colior ETEC – Named for the two toxins it produces and its effects on children who live in areas where the bacteria are infested. Escherichia coli is a common cause of diarrhea worldwide, but strains found in the United States and other high-income countries typically do not have the same toxins as low- and middle-income countries. may produce

A 2020 study by Fleckenstein and Dr. Alaullah Sheikh, then a postdoctoral researcher in Fleckenstein’s lab and now an instructor in medicine, found that one of ETEC’s two toxins, a heat-labile toxin, It was shown that it doesn’t just cause cases of execution. Toxins also affect gene expression in the gut. Increase genes that help bacteria stick to the intestinal wall.

As part of their latest research, Fleckenstein and Sheikh found that the toxin suppresses an entire set of genes associated with the intestinal lining where nutrients are absorbed. The so-called intestinal brush border consists of minute finger-like projections called microvilli, which are densely packed on the intestinal surface like the bristles of a brush. When Fleckenstein and Sheik applied the toxin to a cluster of human intestinal cells, the brush border collapsed.

“There are thousands of microvilli per cell, and instead of being clean, tight and upright, they’re short, floppy and sparse, like most bristles have been plucked out, and what’s left is ragged.” said Sheikh. Who led the 2020 and current research? “That alone negatively affects the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. In addition, we found that genes associated with the absorption of certain vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin B1 and zinc, were also downregulated. may explain some of the micronutrient deficiencies seen in children repeatedly exposed to these bacteria.

Children in low- and middle-income countries tend to have recurrent diarrhea, and the risk of malnutrition and stunting increases with each bout.Studying infant mice, researchers found a single infection with toxin production Escherichia coli It was enough to damage the brush border, but repeated infections severely damaged the intestine and retarded growth.puppies infected with strains of Escherichia coli Those lacking the toxin showed no such intestinal damage or stunting.

If toxins were the problem, Fleckenstein and Sheikh reasoned that a toxin-neutralizing immune response could prevent long-term effects. were vaccinated with the toxin. Lactating mice are too young to vaccinate themselves, but vaccinated mothers produce antibodies that pass to their puppies through breast milk. found that the intestines of infant mice born from .

“This is an argument for developing this kind of vaccine. Escherichia colisaid Fleckenstein. “Repeated childhood infections have lifelong consequences. Immunization, combined with efforts to improve sanitation and access to clean water, can protect children from long-term effects and It gives them the chance to live a long, healthy life.”