Workers and members of the Washington Nurses Association protested the closure earlier this week.

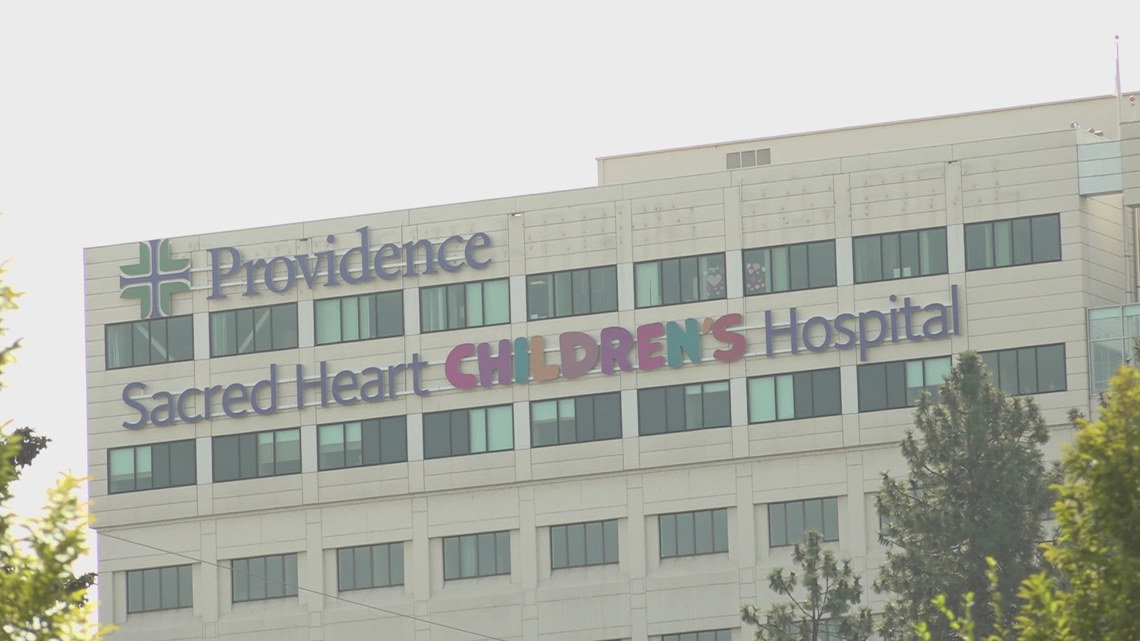

SPOKANE, Wash. — Providence Sacred Heart Hospital’s inpatient adolescent psychiatry unit is closing.

This comes after workers and members of the Washington Nurses Association protested this week against the closure.

The closure of this resource has caused some tension between the union and Providence regarding what is available in the community.

After speaking with the director of the Inland Northwest Behavioral Health Center, he said those who need to be transferred to his clinic instead need not worry.

Providence released a statement saying the unit’s closure will mean it will be unable to accommodate eight patients, down from 22, due to reduced demand from its outpatient programs.

Providence encourages patients who need inpatient treatment to go to local treatment facilities, such as Inland Northwest Behavioral Health.

“We can accommodate up to 27 people per unit,” said Inland Northwest Behavioral Health Director Douglas Hall, “and we can move the beds back and forth, so that means we can accommodate 27 kids in case we have to block a room for any reason.”

Holl said the closures are an issue the mental health clinic can address.

“I can’t speak to the nursing side of things because it’s not my specialty, but I have two nurses,” Hol said. “One is a full-time psychiatrist and the other is a full-time psychiatric mental health nurse that I assign to the unit. Between the two of us, we can easily handle 25 patients.”

Sacred Heart Hospital staff and members of the Washington State Nurses Association, concerned about patients who will be forced to adapt, protested against the closure this week.

“They were concerned about where their patients were going to go,” said Ruth Schubert, director of marketing and communications for the Washington Nurses Association, “especially those patients who have other medical conditions.”

Shubert said the care Sacred Heart Hospital provides to these patients is unique compared to care provided by other healthcare institutions.

“These are people who have autism, developmental disabilities or chronic conditions such as diabetes, and Northwest Behavioral Health can’t provide the care they need,” Schubert said.

Hol wants to set the record straight.

“We can take in patients with diabetes,” Hol said, “patients with asthma and all kinds of other health issues. We have our own medical staff that can handle a variety of health issues.”

Hol isn’t worried about admitting patients, saying his years at the clinic have ensured it will never exceed capacity.

“We have plenty of beds,” Hol said, “and our adolescent unit has never been at capacity.”

KREM 2 reached out to the Washington State Department of Health for numbers on inpatient treatment for young parents but did not receive a response.

Hol reiterated that the clinic will be able to accommodate the number of patients left by Providence’s closure, and he hopes those who need it can get the services they need.