Researchers at Scripps Research have found that chronic alcohol consumption can increase pain sensitivity through two different molecular mechanisms. One is associated with alcohol intake and the other with alcohol withdrawal. This discovery British Journal of Pharmacologyrevealing a complex relationship between alcohol and pain.

Researchers sought to better understand the relationship between chronic pain and alcohol use disorders. They wanted to explore the underlying causes of different types of alcohol-related pain, such as alcoholic neuropathy and allodynia, and how they develop at the spinal cord level. The researchers aimed to investigate the role of microglia, immune cells of the central nervous system, in the development of chronic alcohol-induced allodynia and neuropathy.

Alcoholic neuropathy refers to nerve damage caused by long-term excessive alcohol consumption. This is a type of peripheral neuropathy that affects the peripheral nerves that carry signals between the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body.

Chronic alcohol use can directly damage nerves through nutritional deficiencies and toxins, resulting in symptoms such as pain, tingling, numbness, muscle weakness, and problems with coordination and balance. Alcoholic neuropathy usually affects extremities such as the hands and feet and can seriously affect a person’s quality of life.

Allodynia, on the other hand, is a condition characterized by pain from normally nonpainful stimuli. In other words, the experience of pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli, such as light touch or gentle pressure.

“More than half of patients suffering from alcohol-related disorders develop pain. This is why we focus on the molecular mechanisms that uncover the correlation between pain and alcohol consumption,” said study authors Marisa Roberto and Vittoria Borgonetti. . Scripps Research Institute.

To conduct the study, the researchers divided adult mice into alcoholic mice (heavy drinkers), mice with limited access to alcohol (moderate drinkers), and mice that had never been given alcohol. Three groups of mice were used. They employed a chronic intermittent ethanol vapor paradigm to induce alcoholism in mice. This paradigm involves cycles of alcohol exposure and withdrawal, mimicking the development of alcoholism in humans. Mice then underwent various tests to measure mechanical allodynia and neuropathic pain.

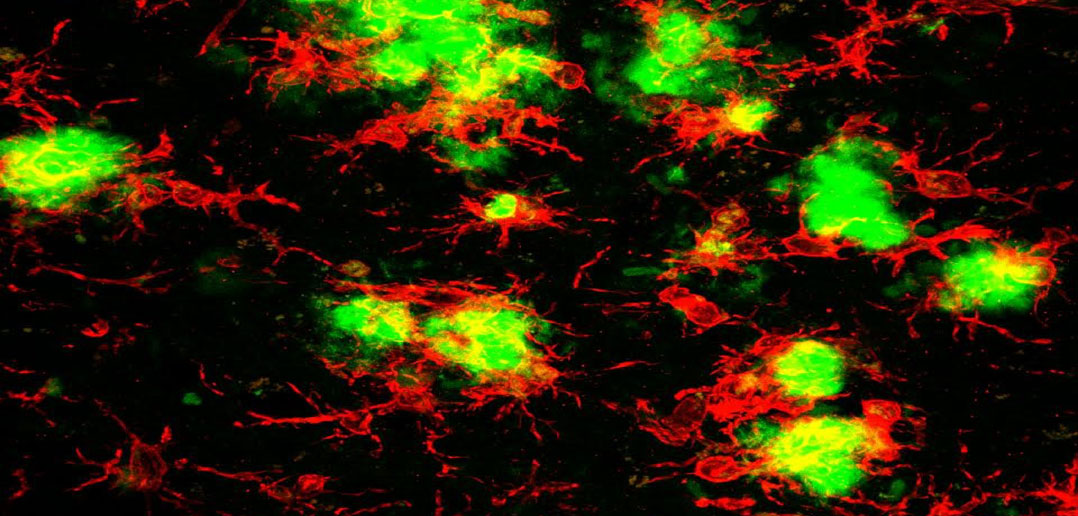

Researchers found that alcoholic mice exhibited higher levels of mechanical allodynia compared to both moderately drinking and non-alcoholic mice. bottom. They also observed changes in protein levels in the spinal cord and sciatic nerves of alcohol-dependent mice, particularly in microglial cells. These changes suggested the involvement of microglial activation and inflammatory processes in the development of alcohol-induced pain.

Researchers also found that there are two different types of pain conditions that result from alcohol use. Mice that were alcohol dependent developed a condition called allodynia. This means that mice became more sensitive to pain during the alcohol withdrawal period. However, when these dependent mice were given alcohol again, their sensitivity to pain was significantly reduced.

On the other hand, about half of the alcohol-independent mice also showed increased sensitivity to pain (hyperalgesia) during alcohol withdrawal. This is similar to what addicted mice experienced. An important difference, however, was that re-exposure to alcohol did not abolish the increased sensitivity to pain in these independent mice. The pain persisted even after being exposed to alcohol again.

“This study highlights two different states of alcohol consumption: heavy drinkers who develop alcoholism, and moderate drinkers who consume alcohol for recreational purposes on a daily basis. These two distinct symptoms are associated with We showed different types of pain: withdrawal hyperalgesia in heavy drinkers who develop addiction and alcohol neuropathy in 50% of moderate drinkers,” Roberto and Borgonetti told PsyPost.

“Hyperalgesia is a temporary pain state, closely associated with alcohol withdrawal, and part of a negative emotional state that usually prompts patients to consume additional alcohol. Persistent and irreversible damage to the sensory system, associated with recreational alcohol consumption and not addiction, so that additional alcoholic beverages do not resolve symptoms and On the contrary, the symptoms will get worse.”

Both of these pain states were accompanied by intense activation of microglia in spinal cord tissue of mice. Microglia are known to play a role in the body’s response to injury and inflammation.

Interestingly, the two pain states appear to involve different pathways within microglia. In addicted mice with abstinence-related hypersensitivity, we noticed increased expression of a protein called IL-6 and activation of another protein called ERK44/42. However, these changes were not observed in mice with alcohol-induced neuropathic pain.

These findings contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between chronic pain and alcohol use disorders and highlight the complex interplay between alcohol consumption, pain and the immune system.

“It’s important to understand the molecular mechanisms that highlight the bidirectional relationship between chronic pain and alcoholism,” said Roberto and Borgonetti. “In fact, although the two forms of pain share intense inflammation, it has been observed that certain inflammatory molecules are increased only in states of withdrawal hyperalgesia and not in neuropathy. It suggests that the two forms of pain may be caused by different molecular mechanisms.”

the study, “Chronic alcohol causes mechanical allodynia by promoting neuroinflammation: a mouse model of alcohol-induced neuropathic pain‘ by Vittoria Borgonetti, Amanda J. Roberts, Michal Bajo, Nicoletta Galeotti and Marisa Roberto.