Behind towering metal gates, the 3.4-acre site in Glendale was once a pioneering mental health facility run by women, for women, but it has lain in disrepair for years.

Now, this city Approved Plans to turn part of the Lock Haven Sanitarium grounds into a mental health museum, estimated to cost about $8 million.

The plan is to renovate a portion of the property known as Pines Cottage, which was built in 1931, preserving its architecture, restoring the surrounding courtyard and landscaping and creating a gathering place.

A conceptual diagram of the place depicts numerous rooms with period-specific furnishings and tells the stories of the women who lived there.

“We want this place to be vibrant and a place that people want to come back to again and again,” Glendale City Councilman Dan Brotman said during Tuesday’s meeting.

Local preservationists say the city council’s move is an important step in reopening the site to the public and bringing its history back into the public’s sights.

But there are concerns the plans could result in the loss of architectural detail and character of the building.

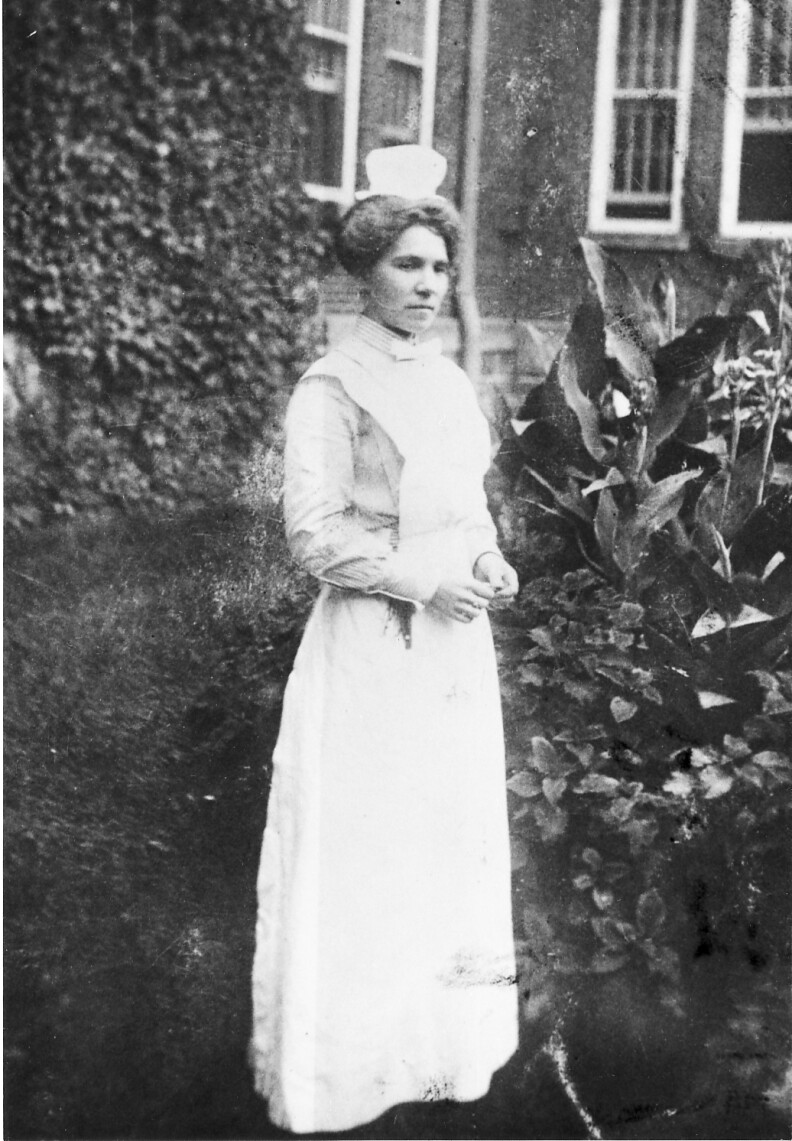

An undated historical photograph of the Lock Haven site.

SWA Group Presentation

)

Compassionate Mental Health Care

When Lock Haven opened in the 1920s, it was revolutionary for its time. It is women run and offers holistic care in beautiful grounds.

Over the years, the facility has treated Hollywood stars such as Billie Burke, who played Glenda in the film “Glenda the Good Witch.” The Wizard of Oz And Marilyn Monroe’s mother, Gladys Baker (aka Gladys Monroe), was called “the sanitarium’s most notorious resident” by our tour guide.

The city of Glendale’s dream of turning the Lock Haven property into a mental health museum is becoming a reality.

“She tried to escape several times,” Joanna Linkchorst, president and co-founder of Friends of Lock Haven, told LAist in 2015. “She made several successful escapes, including one dramatic escape through a small window in a closet, using a bedsheet to tie herself up.”

Historians note that Lock Haven’s founder, Agnes Richards, a psychiatric nurse, was an innovator when it came to compassionate mental health care. Richards was appalled by the conditions she saw while working at Paton State Hospital in San Bernardino and wanted to provide an alternative to the prison-like psychiatric “insane asylums” of the time, where women were notoriously mistreated.

Agnes Richards, founder of Lock Haven Sanitarium.

Courtesy of Friends of Lock Haven

)

So she decided to change her tack.

In contrast to the Gothic dormitories that dominated many state hospitals at the time, Lock Haven featured free-standing cottages with outdoor access, called The Willows and The Coulter, where patients were encouraged to go outside and enjoy the oak trees and carefully tended rose gardens.

Eileen V. Wallis, a history professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, said Richards worked to eliminate the stigma surrounding mental illness, calling those being treated at Lock Haven “ladies” rather than “patients.”

Wallis, who lives in Glendale, A book exploring the history of mental health care in Californiasaid Lock Haven was a safe place where residents could live healthy lives. With a focus on dignified, comprehensive care for women, Lock Haven patients gardened on the grounds and ate meals together in a home-like atmosphere.

“It was very compelling in the sense that it was very different from much of early 20th-century psychiatry, and very distinct,” Wallis says, “but also in the sense that it was very deliberately and consciously gendered.”

She said it’s frustrating to see the facility closed to the public for so long.

Time Capsule

The facility has been closed since the early 2000s. The story of preserving Lock Haven and reopening it to the public as a museum dates back more than a decade.

For much of that time, Linkchorst has worked to save the building from demolition and neglect, and when the public was allowed on the grounds, she gave tours of the building and 15 other buildings, bringing to life the story of Agnes Richards, pointing out architectural details and sharing at least two ghost stories.

The centerpiece of Lock Haven’s grounds is a 1921 sculpture called the Reclining Nude, which serves as the site’s mascot. The statue represents one of California’s oldest pottery manufacturers. Gladding McBean.

Link-Choust named it “The Lady of Lock Haven.”

The Lady of Lock Haven

She said she’s glad to see the city slowly reopening the place to the public, but worries that the approved design plans will remove features such as colorful 1930s bathroom tiles and other period-specific details that make it, in her words, a “time capsule.”

“I really hope I never touch it because once it’s gone, you never get it back,” she said.

The Rockhurst site It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Link-Chorst hopes to eventually invite young women back for a tour of the facility, where they can learn important lessons about mental health and how people living with mental illness can be treated humanely, she said.

A current photo of Lock Haven.

“For a lot of people, it’s hard,” she said, “and the way we deal with these women is to remove them from the situation, treat them with dignity, and let them go home stronger and more able to deal with it.”

What’s next for Lock Haven?

The Glendale City Council on Tuesday unanimously approved plans to turn the building known as The Pinesville into a museum. The motion directs city staff and design firm SWA Group to move forward with developing construction drawings and a bid package.

SWA design drawings for the Pines Courtyard renovation.

The development comes about three years after state Sen. Anthony Portantino secured $8 million from the state to transform the property into a mental health museum. The city purchased the property in 2008 for $8.25 million.

“Transforming the Lock Haven site into a museum that tells the story of Agnes Richards’ legacy, women’s history and compassionate care for women with mental illnesses will allow us to honor the historical significance of this site and the legacy of the people who created it.” Portantino in 2021.

The project must be completed by March 2026 to avoid losing state funding.

Have a question about mental health in Southern California?

One of my goals in the mental health field is to make the seemingly unmanageable mental health care system more manageable.