- Some experts estimate that it will take 20 to 25 years to address the school psychologist shortage. The country needs 60,000 more school psychologists to meet the recommended ratio.

- The national ratio for the 2021-2022 school year was 1,127 students per school psychologist. Her only state, Utah, meets the recommended 1:500 ratio.

- Experts say further cuts to the Department of Education as Congress negotiates spending would be devastating.

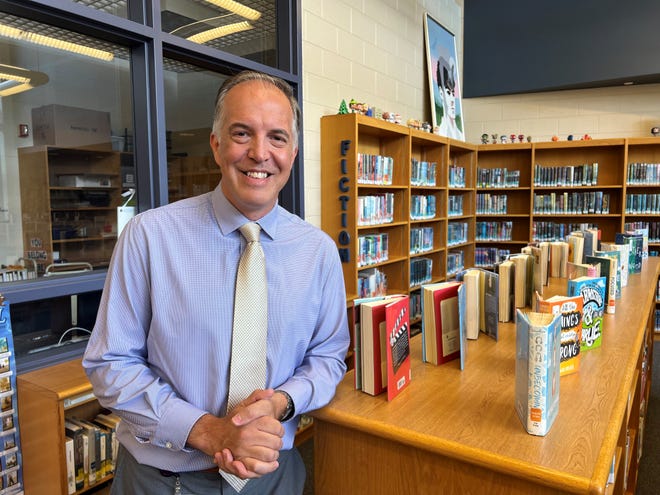

HERSHEY, Pennsylvania — Jason Pedersen takes eight minutes to walk between elementary and middle school in the Derry Township School District in Hershey, Pennsylvania. He works as one of three school psychologists district-wide.

“I’m across the street from two buildings, but thankfully it’s only an eight-minute walk away, unlike some people who have to drive miles and miles. It impacts your ability,” he told USA TODAY. “It’s still a challenge.”

If a student in one building needs him and that student is in the other, he may not be in the right place at the right time, Pedersen said.

“I may not be here when someone needs me,” he said from the district’s middle school, days before the start of the 2023-2024 school year.

National Association of School Psychologists recommend the ratio One school psychologist for every 500 students. In the Derry Township School District, the ratio is more than double, at 1 to 1,100.

Experts told USA TODAY that the shortage of school psychologists, school counselors and school social workers has been a problem for decades, but has worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a resurgence in school shootings. He said it became noticeable. There is now increasing pressure on school districts to support students with these resources.

Pedersen and school administrators in the Derry Township School District are developing a strategy to come up with best practices for providing mental health services to students despite staff shortages and a lack of funding for permanent staffing. It’s standing up. The district has contracted with agencies to provide school-based outpatient treatment, established a concierge service to connect students with mental health professionals, and provided school psychologists with guidance on what treatment to provide. They are finding unique and innovative solutions, such as using a multi-layered support system that acts as a framework. Be intentional about using the resources you have to support your students.

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill are proposing answers for how to deal with the problem. But with Congress extending government spending deadlines until November and negotiations continuing without a permanent speaker in the House of Representatives, the question remains whether America’s schools will receive what they need for adequate mental health resources. remains in limbo.

1 in 5 children According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many people experience mental health disorders each year. Many of these children receive no services at all, and 70 to 80 percent of those who do receive services at school, the report says. National Association of School Psychologists.

Some House Republicans are considering cutting billions of dollars from the Education Department during the appropriations process.of White House estimates cuts There could be up to 40,000 fewer teachers, teaching assistants and other key staff in schools across the country. Other lawmakers and advocates are pushing to pass legislation that would fund additional mental health resources for school districts and create a permanent funding source for these services.

“We expect schools to do more for our children than we probably expected 50 years ago, but we expect schools to do more for our children than we expected 50 years ago, but the kinds of resources that schools need ,” said Lynn Bufka, associate director of practice change at the American Psychological Association. .

What experts recommend

Experts recommend that each school district have a trio of school counselors, social workers and school psychologists working together to provide mental health services to students.

But that rarely becomes reality.

According to Amanda Fitzgerald, deputy executive director of the American School Counselor Association, school districts across the country are also experiencing a shortage of school counselors.

School counselors focus on post-secondary work, including helping students apply to college and succeed after high school. They often perform basic mental health services, such as holding grief groups and offering anti-bullying programs.

If a student requires more intensive services, a school psychologist, if available, will be involved. However, if a school district does not have a school psychologist or is too busy, school counselors often have to fill in.

American School Counselor Association Recommended ratio of 250 students According to the school counselor.

“If we were to go from 1 to 250 staff across the country, there would definitely not be enough school counselors to fill those positions, and it would only get worse in some places,” Fitzgerald said. , added that rural areas are facing even more acute shortages.

Why do stockouts occur?

Experts told USA TODAY the shortage is due to two issues. One is a permanent lack of funding for school districts, and the other is the rising cost of higher education programs for future mental health workers.

Kelly Vaillancourt Strobach, director of policy and advocacy for the National Association of School Psychologists and a school psychologist herself, said the shortage has been an ongoing problem for decades.

Professor Strobach estimates that it will take 20 to 25 years to address the shortage of school psychologists. The country needs 60,000 more school psychologists to meet the recommended ratio.

The national rates for the 2021-2022 school year are as follows: 1,127 students per school psychologist. Her only state, Utah, meets the recommended 1:500 ratio.

Becoming a school psychologist is not an easy path, Strobach said. Most working school psychologists have a Ph.D., but that requires an internship, which many school districts cannot fund. This makes it difficult for aspiring psychologists to pay for free graduate school tuition, living expenses, and even moving costs to relocate to work in the district.

A shortage of school psychologists deprioritizes other responsibilities.

Because school psychologists are required to complete evaluations of students for special education services, they are often focused primarily on completing evaluations and have limited opportunities to provide additional support.

“It seems like we always hear these calls and big movements around addressing post-crisis shortages…These people are there to do more than just deal with the crisis. ” Strobach said.

Permanent funding needs

Kari Owen is the school psychology program director at the University of South Dakota in a city of 12,000 people. The university received his $3 million grant to use over the next five years to conduct a statewide needs assessment. This funding comes from the bipartisan Safe Communities Act passed during the pandemic.

The school psychology program has only three full-time faculty members and is the only training program in the state.

South Dakota’s ratios are: 1 school psychologist for every 1,650 students − 3 times the recommended ratio. Owen said one of his colleagues travels 900 miles a month across the state to ensure children receive quality school mental health services.

Bipartisan Safer Communities Act Funded two grant programs Address mental health resources in schools across the country over the next five years. One grant focuses on training future mental health providers by funding entry-level programs and providing loan forgiveness and tuition. The other would provide grants to districts and states to hire and retain mental health providers.

“Ideally, this would be annual money that would be available to everyone,” Strobach said.

Experts like Strobach say one-time grant funding won’t address the long-term problem of solving these shortfalls. They want Congress to address this problem by funding more permanent solutions, such as regular training programs, annual grants, or legislation requiring paid internships for school psychologist candidates. It is claimed that it will be able to assist in dealing with

In Pennsylvania, the state legislature recently Bill passed to make internship grants permanent and the recurrent line of the national budget. School districts can now apply for funding through the state to pay for interns.in ohio Similar programs.

legislative efforts

Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Ga.; We sponsored the promotion of student services in today’s schools.or the ASSIST Act, was enacted earlier this year to help schools increase the number of mental health and substance use disorder specialists.

Warnock said the shortage of mental health providers is a problem not only in Georgia but across the nation. He added that more focus needs to be placed on funding issues and pipeline issues to train young people.

“Mental health is health care and not understanding that is a problem when it comes to mental health care, not just for students but for the general public,” he said.

Warnock’s colleagues have introduced similar bills to address the shortage.

Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D.N.H.) Bipartisan School Mental Health Excellence Act Last May, the Department of Education was given the power to partner with higher education institutions to fund graduate programs for future school mental health workers.

“This is a long-term challenge, so I don’t think there’s any time to waste,” she told USA TODAY.

Shaheen, a former teacher, said she was always concerned about the overall well-being of her students, not just what they were learning in the classroom.

“If we don’t address mental health issues when they present themselves, it will impact and ultimately cost us our ability to earn a decent living and access the opportunities we need to succeed in school and beyond.” “You get more money in the long run,” she said.

In the House, Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, Republican of Pennsylvania, and Rep. Jared Golden, Democrat of Maine, are leading companion legislation to the bill.

Rep. Jamal Bowman (D.N.Y.) said counselors are just as important as teachers and administrators, and in some cases even more important.

Bowman, a former middle school principal in the Bronx, called the staffing shortage “disastrous.” He recalled witnessing an increase in suicidal ideation and self-harm among students in his previous role. When the school first opened in 2009, he decided to hire a social worker and school counselor even before hiring a vice principal.

“This crisis is a life-or-death crisis in terms of the shortage of counselors, social workers and school psychologists,” he said.

Bowman said there needs to be policies that consistently fund schools fairly, regardless of Democratic or Republican leadership.

“I think (this is) a powerful thing that we absolutely have to do,” he said.

“Puzzle that fits”

Returning to Hershey, Pennsylvania, Pedersen worked as a school psychologist for more than 25 years, including 15 years in the Derry Township School District.

In addition to three psychologists, the Derry Township School District has one social worker and 11 school counselors, who focus on day-to-day interactions with students. Pederson said he sees all his roles as “puzzles that fit together.”

Stacey Winslow, Superintendent of the Derry Township School District, said, “Public education is key to a democratic society and is in the best interest of our people, and as a nation we strive to provide effective resources to as many students as possible.” It’s also our best bet.”

“Paying for mental health services for eight-year-olds is much more cost-effective than for adults,” Pedersen added.