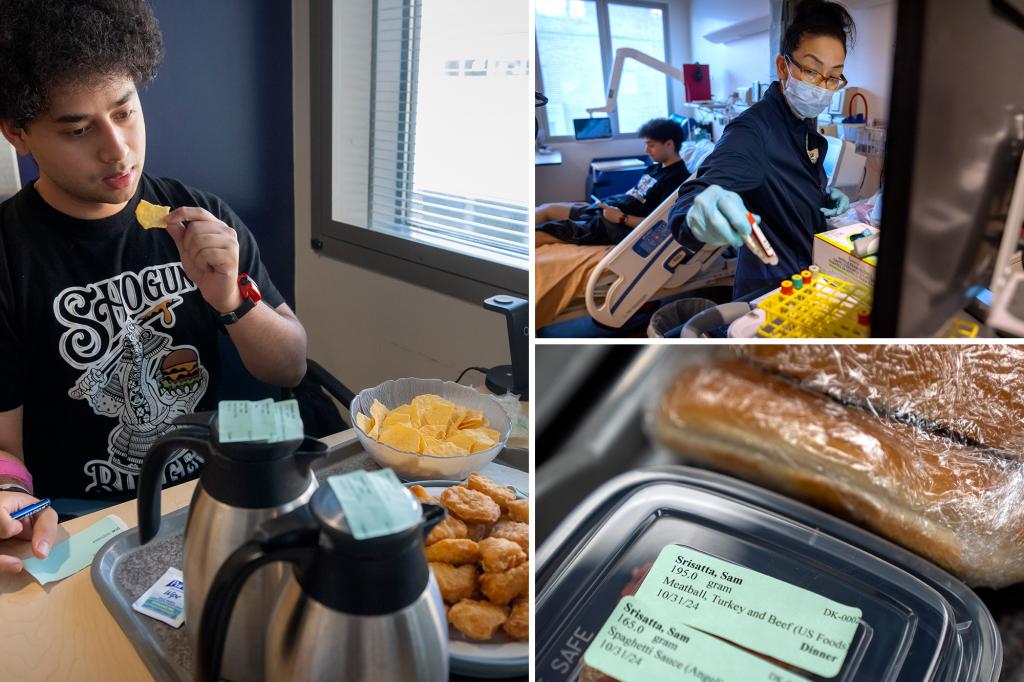

Sam Srisatta, a 20-year-old University of Florida student, lived here for a month last fall, playing video games and allowing scientists to record all the food they had in their mouths.

From large bowls of salads to large platters of meatballs and spaghetti sauce, Srisatta has sniffed his path through nutritional research aimed at understanding the health effects of ultra-highly processed foods.

He allowed the Associated Press to tag together for a day.

“Today, my lunch was chicken nuggets, some chips, some ketchup,” said one of three dozen participants, paying $5,000 each to devote 28 days of life to science.

“It was pretty fulfilling.”

Examining exactly what made these nuggets so satisfying is the goal of a widely anticipated research led by Kevin Hall of the National Institute of Health and Nutrition.

“What we want to do is to get a better understanding of the process, so we can better understand it,” Hall said.

Hall’s study relies on patients’ 24/7 measurements rather than self-reported data to investigate whether ultra-positive foods can eat more calories and gain weight, leading to obesity and other well-documented health issues. And if so, how?

When Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. makes nutrition and chronic illness a key priority, the answer won’t come anytime soon.

Kennedy has repeatedly targeted processed foods as the main perpetrator behind the various illnesses that afflict Americans, especially children.

He vowed at a Senate confirmation hearing that they would focus on removing such food from school lunches for their children as they are “going sick.”

Just as the rates of obesity and other diet-related illnesses have also risen, in recent decades, ultra-highly processed foods have exploded in the US and elsewhere.

Foods that are often high in fat, sodium and sugar are usually cheap and mass-produced, and contain colors and chemicals that are not found in home kitchens.

Think sweet cereal and potato chips, frozen pizza, soda, ice cream.

Research has linked ultra-highly processed foods to negative health effects, but it remains uncertain whether it is a real food treatment, not the nutrients it contains or anything else.

small 2019 Analysis Hall and his colleagues found that ultra-positive foods began to eat about 500 calories per day than participants had eaten a matched meal of unprocessed food.

The aim of the new research is to replicate and expand on the research and test new theories about the effectiveness of ultra-highly processed foods.

For one, some foods contain attractive combinations of ingredients such as fat, sugar, sodium, and carbohydrates.

The other is that foods contain a lot of calories per bite, allowing you to consume more without realizing it.

Teasing these answers requires the willingness of volunteers like Srisatta and the know-how of health and diet experts to identify, collect and analyze the data behind the estimated millions of dollars of research.

During the month at the NIH, Srisatta equipped with monitors on his wrists, ankles and hips, tracking all movements and regularly giving up 14 blood.

Once a week, he spent 24 hours in the metabolic chamber. This is a small room equipped with sensors to measure how his body uses food, water and air.

He was allowed to go outside, but the director only had to prevent whimsical snacks.

“It really feels so bad,” Srisatta said.

He could eat as much as he wanted.

Sara Turner, NIH nutritionist who designed the food plan, said that moving meals in the room were prepared three times a day, three times a day.

In the basement of the NIH Building, teams carefully measured, weighed, sliced and cooked food.

“The challenge is to make all the nutrients work, but you still need to get your appetite pounding and look great,” Turner said.

The trial results are expected later this year, but the preliminary results are interesting.

At a scientific conference in November, Hall reported that the first 18 test participants ate an ultra-subtle, energy-dense, ultra-high transplant meal, with about 1,000 calories a day, especially overcrowded and more concentrated than those who ate minimally processed foods, leading to weight gain.

When these qualities were corrected, consumption was reduced even if the food was considered super positive, Hall said.

Data is still collected from the remaining participants and must be filled out, analyzed and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Still, the early results suggest “energy intakes “you can almost normalize” despite the fact that they still eat more than 80% of the calories from ultra-positive foods,” Hall told the audience.

Not everyone agrees with Hall’s method or the meaning of his research.

Dr. David Ludwig, an endocrinologist and researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital, criticized the 2019 study as “a fundamentally flawed in a very short period of time.”

Scientists have known for a long time that people can feed more or less in a short time, but their effects have faded quickly, he said.

“If they last, there will be an answer to obesity,” Ludwig said. He has long argued that highly processed carbohydrate consumption has been a “major dieter” and focuses on food processing.

He sought larger designed research that lasts for a minimum of two months, and the “washout” period separates the effects of one meal from the next. Otherwise, “We waste our energy and mislead science,” Ludwig said.

Concerns about the short length of the study may be effective, said Marion Nestle, a nutritionist and food policy expert.

“To solve that, Hall needs funding to do longer research with more people,” she said in an email.

According to Senate documents, NIH spends around $2 billion a year on nutrition surveys, about 5% of its total budget.

At the same time, agents reduce the ability of the metabolic unit to conduct such research, reducing the number of beds that researchers have to share among them.

The two currently enrolled at the centre and the two planned for next month are the most holes to study at once, adding several months to the research process.

Srisatta, a Florida volunteer who wants to become an emergency room doctor, said he wants to learn more about how processed foods affect human health after taking part in the trial.

“I mean, I think everyone knows it’s better not to eat processed foods, right?” he said.

“But we have evidence to support it in a way that is easy for the public to digest,” he said.

HHS officials did not answer questions about Kennedy’s intentions regarding nutrition research at the NIH.

The agency, like many others in the federal government, is being eased by the wave of cost reductions directed by President Donald Trump and his billionaire aide Elon Musk.

Jerold Mande, a former federal food policy advisor for the three administrations, said he supports Kennedy’s goal of addressing diet-related illnesses.

He promoted the proposal for a 50-bed facility where government nutrition scientists could house adequate researchers like Srisatta and allow them to rigorously determine how a particular diet would affect human health.

“If we’re going to make America healthy again and deal with chronic illnesses, we need better science to do that,” Mande said.