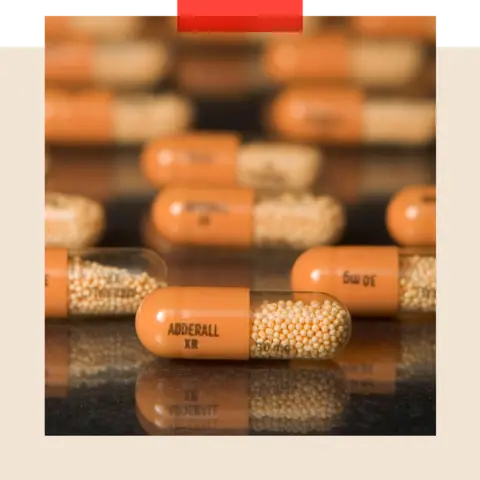

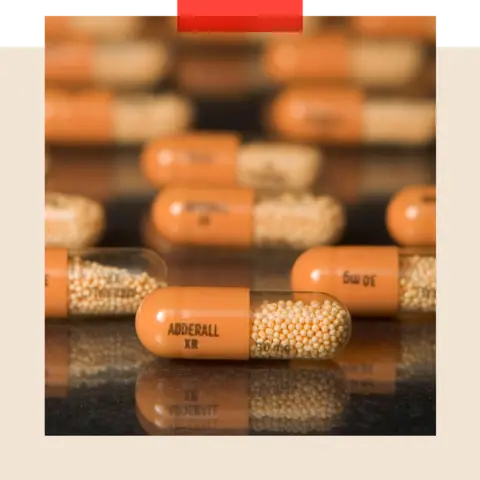

The number of people taking ADHD medication is at an all-time high and the NHS is struggling to diagnose and treat the condition.

Since 2015, the number of people in England being prescribed medication for ADHD has almost tripled. BBC investigation They suggest it would take eight years to assess all adults on the waiting list.

Last year, ADHD was the second most visited condition on the NHS website. Concerns about this increased demand have led the NHS in England to Launch a task force.

So what’s going on? And where will it end? Is ADHD becoming more common? Are we simply becoming more aware of it? Or is it being overdiagnosed?

It’s not just you and me who are surprised; it seems the experts were too.

“No one expected the massive surge in demand over the last 15 years, but particularly the last three,” says Dr Ulrich Muller-Sedgwick, ADHD advocate at the Royal Association of Psychiatrists, who has run an adult ADHD clinic since 2007, when there were only a handful of clinics available.

ADHD is a fairly new condition – the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) only officially recognised it in adults 16 years ago – and Dr Muller-Sedgwick argues that when considering whether ADHD is likely to continue to rise, we need to take into account two different concepts: prevalence and incidence.

Prevalence is the percentage of people who have ADHD. Dr Muller-Sedgwick predicts it will remain roughly constant at 3-4% of adults in the UK.

Incidence rates are the number of new cases, or people who are diagnosed. That’s where we’re seeing an increase. “What’s changed is the number of patients we’re diagnosing. The more we diagnose, the more word gets around,” he explains.

This is agreed by Professor Emily Simoff, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the King’s Maudsley Children and Young People Partnership. She believes around 5-7% of children in the UK have ADHD, saying it’s “broadly the same across the world, it’s consistent and there’s really no increase”.

Prof Simov agrees there has been a “surge” in people seeking assessments since the pandemic, but says this comes after a “long-standing lack of awareness” over many years.

She points to statistics on ADHD medication: she expected around 3-4% of children in the UK would need ADHD medication, but in reality only 1-2% are on it, which she thinks shows we’re still underestimating the scale of the problem.

Professor Simoff explains: “I think this is an important starting point when we ask: ‘My goodness, why do so many kids now have ADHD? Are we over-diagnosing ADHD?’ For many years ADHD has been under-diagnosed and under-recognised in the UK.”

In other words, we can expect to see more people being diagnosed with ADHD in the future as services catch up.

“Hump”

Thea Stein is chief executive of the Nuffield Trust, a health think tank. She describes the recent increase in demand as a “hump”. She says: “Knowledge and visibility have increased the desire to be diagnosed and to be diagnosed. [it’s as] It’s that simple.”

Stein says the most immediate challenge is understanding and overcoming the huge numbers of people on ADHD waiting lists. And in the longer term, she believes society will be able to identify ADHD in children earlier, which she hopes will mean they can get better support at an early age and reduce the strain on adult services.

“I’m really optimistic that we’ll get through this and be in a much better place as a society,” she said. “What makes me less optimistic is that this is a temporary solution.”

ADHD may be a new concept, but people who struggle to concentrate are an age-old problem.

In 1798, Scottish physician Sir Alexander Crichton wrote about a “disease of attention” involving “extraordinary mental restlessness.”

He explained: “When people are affected in this way, they say they become restless.”

But ADHD is more than just concentration problems and hyperactivity: People with ADHD can also have trouble controlling their emotions and impulses. ADHD has also been linked to substance abuse, financial difficulties, higher crime rates, and even car accidents.

Every expert I spoke to strongly agrees that it’s far better for people with ADHD to be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

“There’s a risk of a very bad outcome,” says Dr Mueller-Sedgwick, but her eyes light up when she explains how diagnosis and treatment can be life-changing.

“I have seen many patients recover and return to work or education,” he says, “and I have seen parents become better parents after going through the family court process.”

“That’s why we work in this field. Working in the mental health field is really rewarding.”

A treatment breakthrough

Currently, treatment for ADHD revolves around medication and therapy, but other options are emerging.

A patch (connected to a device that sends stimulation pulses to the brain) that children with ADHD can wear on their forehead while they sleep is now on sale in the US. It is not prescribed in the UK, but researchers here and in the US are working on clinical trials investigating it.

Professor Katia Rubia is Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at King’s College London and she said: “My research over the last 30 years or so has essentially been about imaging ADHD and understanding what is different in the brain. [of people with ADHD].”

Rubia explains that certain parts of the brain, including the frontal lobe, are slightly smaller and less active in people with ADHD. He is trying to activate these parts of the brain, and he is working on the trigeminal nerve, which has a direct connection to the brain stem and can increase activity in the frontal lobe.

“This is all very new,” she says, and if we find that it works, we have a new treatment,” but she adds that it’s unproven, but “if all goes well, it could be on the market in two years.”

So, it is hoped that in the not too distant future there will be more ways to treat ADHD without medication. But the immediate challenge is getting over the “mountain” of people waiting to be diagnosed. Over time, the rise in diagnoses should decrease.

For support regarding ADHD issues, see BBC Actionline.

Top photo: Getty Images

BBC In-Depth is the new home of our website and app, bringing you the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under our distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that question assumptions and in-depth reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. We’ll also be showcasing thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We start small, but think big. We want to hear what you think. Click the button below to send us your feedback.