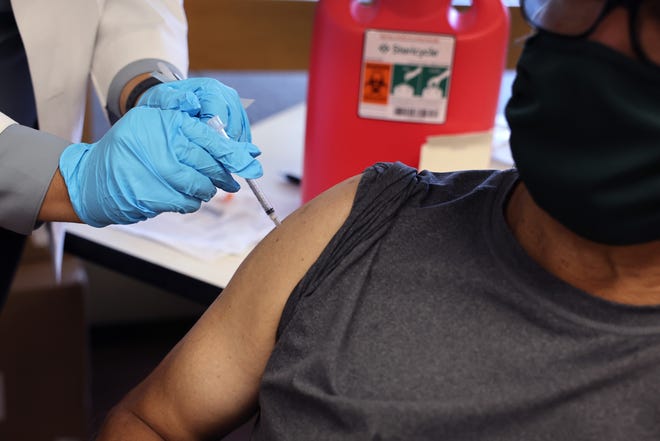

When COVID-19 vaccines entered the commercial market last fall, the federal government created a program to help people with limited coverage or the uninsured get vaccinated. Introduced. The program, which provided millions of free shots to low-income people, is now being shut down, U.S. health officials say.

The Bridge Access program is set to end in August, months earlier than local health departments and health centers expected, as pandemic-era funding from Congress expires. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention official said in an email that Biden administration officials are seeking permanent funding to allow routine vaccinations for adults to remain free through a program similar to the long-standing childhood vaccination program.

Access to Health:Imagine if the government provided dental care. New federal rules could make that a reality.

Health center and health department leaders Bridge Access ProgramThey’re concerned about how to secure funding for a vaccine in time for the winter respiratory virus season, when hospitalizations and deaths tend to rise. Many low-income Americans may not be able to afford a vaccine against COVID-19 and its myriad variants. Updated vaccines targeting those strains are on the way, but pandemic-era funding will be lost.

“Money isn’t infinite, but COVID-19 is still with us,” said Whittier Street Health Center, CEO of Whittier Street Health Center, a federally qualified medical center that primarily serves Boston’s low-income communities of color. Frederica Williams said. The program leverages Bridge Access funding for vaccinations.

Williams said about one-fifth of the center’s patients are uninsured, including many new immigrants from Haiti and Central and South America. This does not include people who have health insurance but do not have vaccine coverage, such as rideshare drivers and restaurant staff.

CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen last fall Visit to Whittier Street Health Center To promote the updated COVID-19 vaccine, the health center launched a Bridge Access Program. Williams was surprised by the sudden halt in funding. As of this week, the health center had not received any notice of the end of the Bridge Access Program, she said.

Leaders of the National Association of Community Health Centers, a nonprofit advocacy group, said they knew the program was temporary but were surprised to hear it would end this August. Sarah Price, the association’s director of public health integration, said in a statement that health centers will continue vaccinating people daily as this cold season brings an increase in looming respiratory illnesses like influenza, RSV and COVID-19. “Health centers will either stock these vaccines or refer them to resources within their communities, with the goal of addressing access barriers and closing the loop,” she said.

Since its launch on September 13, 2023, Bridge Access has distributed more than 1.4 million free doses of COVID-19 vaccines through pharmacies, community health centers, and public health departments across the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). spokesperson David Daigle said in an email. The CDC did not respond to inquiries about whether it had informed health centers or public health departments that the bridge program would end in August.

“While there may be small amounts of free vaccine available through the Health Department’s vaccination program beginning in August, supplies will be very limited,” Daigle said in the email, which was first shared on social media. CBS News reporter. “It remains to be seen whether the manufacturer will have a patient assistance program.”

Vaccine manufacturers Novavax and Pfizer said in an email that they are evaluating vaccine availability options for U.S. consumers in light of the changes and are making sure that uninsured and underinsured patients have access to the vaccine. He said he plans to do so. Moderna did not respond to a request for comment.

When a federal panel broadly recommended an improved version of the vaccine in September, many people hit a wall trying to pay for it. Major pharmacies in the US were charging more than $100 per dose. At the time, the Bridge Access Program was a pioneer in providing vaccinations to people who couldn’t afford it, and was cited by many on social media.

The end of the program has health officials concerned about an increase in infection numbers.

“This is creating a barrier that could lead to a larger resurgence of COVID,” said Dr. Walter Orenstein, associate director of the Emory University Vaccine Center. Dr. Orenstein previously worked as the director of the National Immunization Program. Vaccine programs for children started in the 1990s And he predicts problems will arise unless vaccines become more readily available.

“I hope I’m wrong, but I think it’s better to remove barriers to access to vaccination than to make people unwilling to get vaccinated when we have a safe and effective vaccine.” think.”

mental health:What can prevent suicide?A place to call home, someone to reach out to.

The number of uninsured people in the U.S. is at an all-time low Ministry of Health and Human Services The report was released in August. However, about 7.7% of the population, or about 25 million people, still lack health insurance. Among adults aged 18 and older, 11% are uninsured. Experts say many of the uninsured are people of color and immigrants. The uninsured also tend to be young, low-income, and live in southern states that have not expanded Medicaid access. This demographic group includes millions of undocumented immigrants who are not covered by federal health insurance.

Additionally, millions of adults lack adequate health insurance through their employers, and many earn too much to qualify for Medicaid — categories of people who would likely have had a harder time receiving a COVID-19 vaccine without Bridge Access funding.

Vaccine funding comes as Medicaid is being scaled back across the U.S. About 22 million people who had Medicaid coverage during the pandemic were disenrolled as of May 10. KFFa nonpartisan health policy organization.

North Carolina is an exception, with the state legislature expanding Medicaid to adults in late 2023. The state has experienced a smaller decline in Medicaid enrollment than any other state in the country. Raynard Washington, public health director for Mecklenburg County, which includes Charlotte, said the state paid for the preventative vaccines.

According to Washington State, about 13% of the county’s adult population is uninsured. These patients are disproportionately Latino and foreign-born. Many of the county’s underinsured people have also been vaccinated, but they work jobs without benefits or earn enough money to qualify for Medicaid.

Washington, who chairs the Metropolitan Health Coalition, a consortium of top U.S. health officials, believes Congress should work to improve the public health system instead of chipping away at efforts put in place since the pandemic. There is. He said it’s important to invest in vaccines to protect yourself and yourself.

He said it was important to invest in vaccines to protect ourselves and those at risk of severe illness.

“Of course, in the case of COVID-19, we know that there are still some people who are very vulnerable to severe disease,” Washington said, “so in many ways, these vaccines are saving some people’s lives.”

A coalition in Washington supports the Biden administration’s adult vaccine proposal, which failed to pass.

He said now is not the time to back down from preventing coronavirus infections.

“You have to invest in times of crisis and times of non-crisis,” he said.

The next generation of COVID-19 vaccines (targeting the dominant strain) have not yet been released. If that happens, Washington state expects local and state jurisdictions to cover the costs with other sources.

At the Whittier Street Center in Boston, Williams said she recently received a call from two patients who had tested positive for COVID-19.

The Williamses met through a local church program and asked about antiviral drugs available through the state Department of Public Health. Two people did not have insurance. The Williamses said the program they are inquiring about ended in March, but that the Whittier Center will cover the cost of treatment regardless of whether they have insurance or not.

Even if the pandemic eases, the need for care will still remain, she said.

“As we have always done, we must continue to find ways to remain true to our mission,” she said.