The Food and Drug Administration is expected to propose changes to prepackaged foods sold in the US that would require key nutrition information to be displayed on the front of the package, in addition to the Nutrition Facts label already on the back.

The concept, designed to quickly inform busy consumers about the health effects of the foods and drinks they are considering purchasing, is not new. Dozens of countries Nutrition facts labels are already being used on the front of packaging in a variety of designs: in Chile, for example, a stop sign is painted on the front of a product to indicate if it is high in sugar, saturated fat, sodium or calories, in Israel such foods and drinks have red warning labels, and in Singapore drinks are graded based on their nutritional value.

Advocates have been urging the FDA to mandate front-of-package labeling for nearly two decades to encourage people to make healthier choices and encourage food manufacturers to refine recipes and put fewer warnings on their products. The FDA was largely silent on the issue until it announced its intention to consider front-of-package labeling as part of a national health strategy unveiled at a groundbreaking White House conference on hunger, nutrition, and health in 2022. Since then, the FDA has reviewed literature on front-of-package labeling and conducted focus groups to test label designs.

But the idea faces opposition from trade groups representing U.S. food and beverage manufacturers, which created their own voluntary system for placing certain nutrient claims on the front of packaging more than a decade ago, and some of the label designs the FDA is considering could be challenged on First Amendment grounds.

“The United States has a broader interpretation of freedom of speech than any other country in the world, and it is more inclusive of corporate speech,” said John F. Kennedy, an associate professor at the New York University School of Global Public Health. Researched First Amendment obstacles to mandating front-of-package food labels.

Her research shows that purely factual designs (such as those listing the grams of added sugars) are more likely to be deemed constitutional than interpretive designs with shapes or colors that characterize the product as unhealthy.

“When it becomes subjective, it becomes even more suspicious,” Pomerantz said.

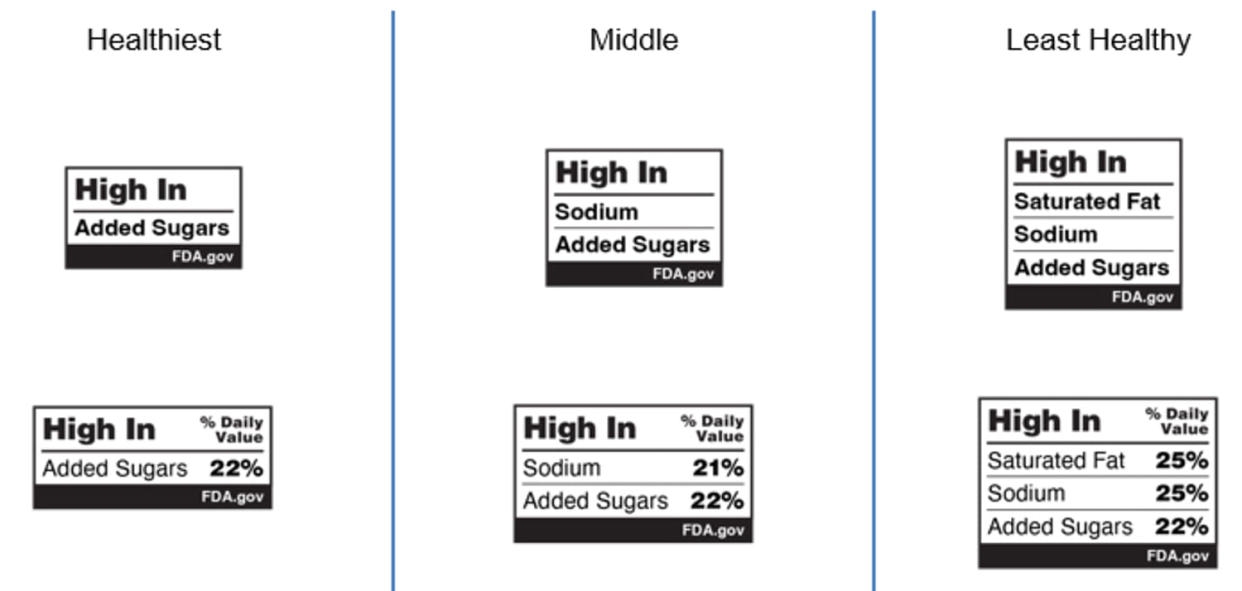

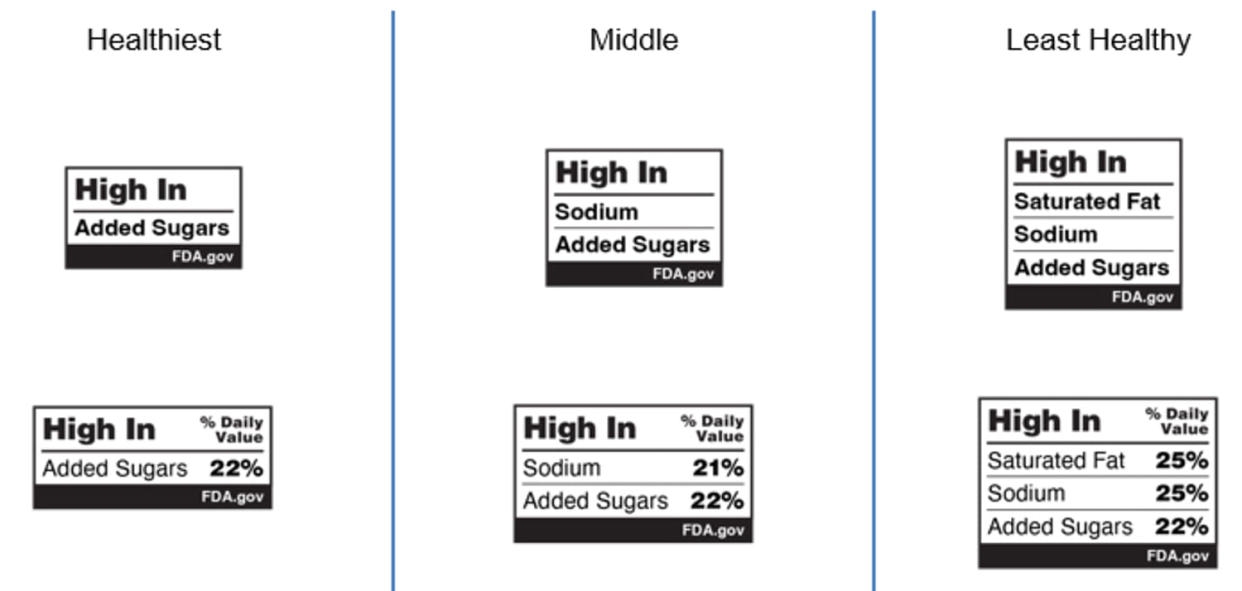

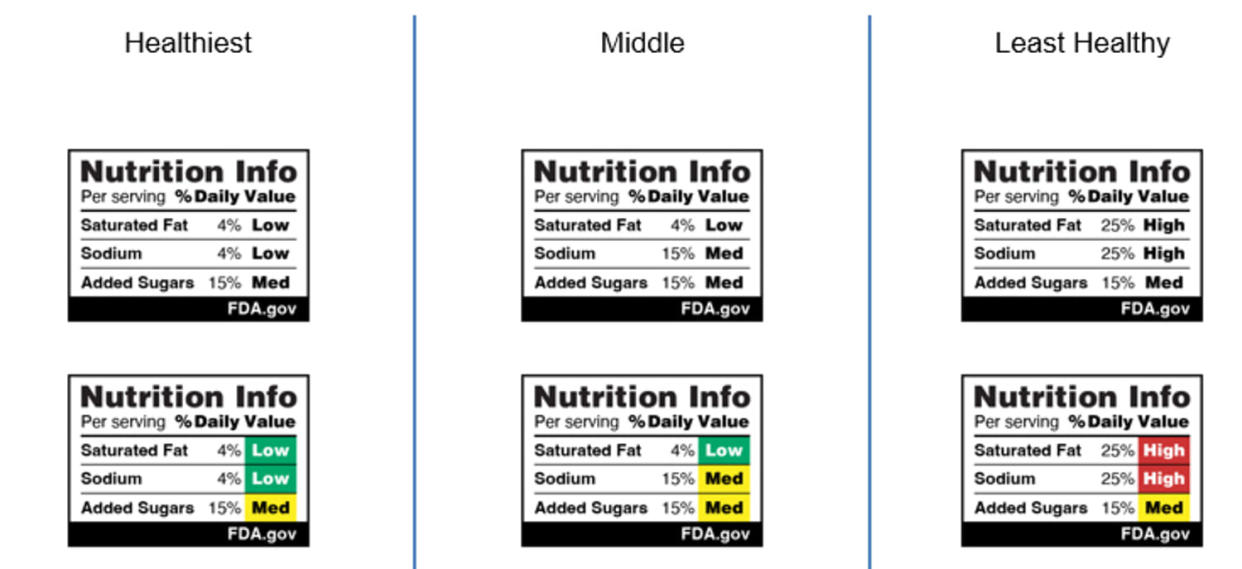

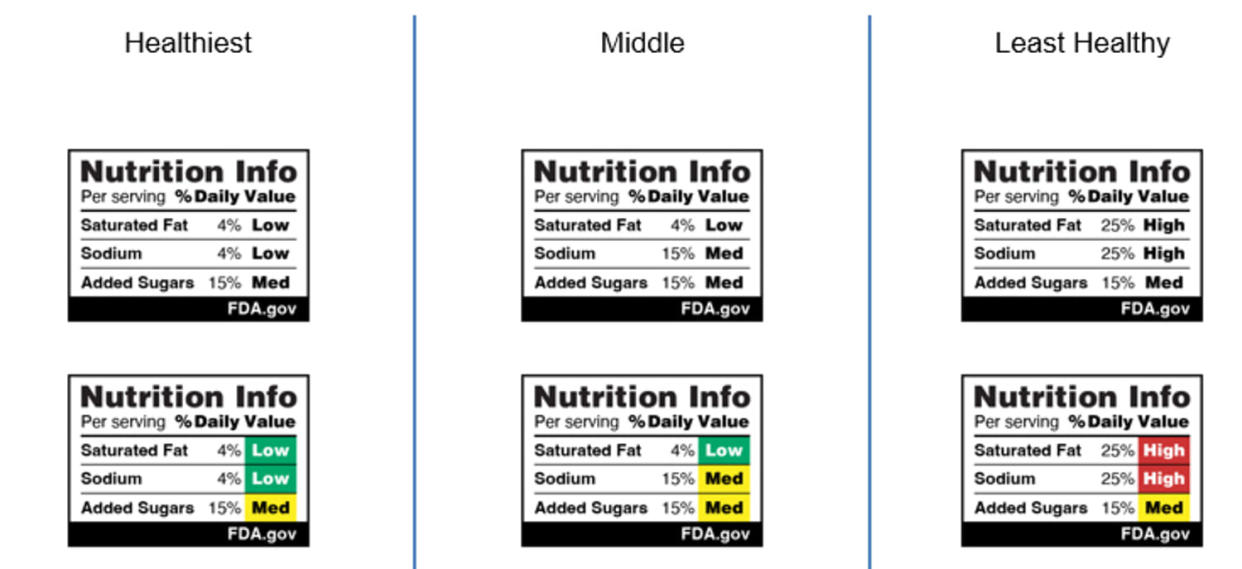

Between Multiple Label Options Some of the products the FDA tested used traffic light colors to indicate whether they were high (red), moderate (yellow), or low (green) in saturated fat, sodium, or added sugars, and some also stated whether the product was “high” in those nutrients, adding the percentage of the recommended daily value provided by one serving.

An FDA spokesperson declined to say which label design will be used when speaking to NBC News, nor could they say exactly when the FDA would publish its proposed rules, other than to say the agency is “targeting this summer,” despite a previous deadline of this month.

The Consumer Brands Association and the food industry association FMI have launched a voluntary labeling system for the food and beverage industry called Facts up front Since its inception in 2011, commissioners of the Food Safety Commission have made clear that they oppose mandatory interpretive designs like the red light/green light system. Interpretive labels “create unnecessary fear in consumers based on a single limiting nutrient without providing meaningful information about how the food fits into an overall healthy dietary pattern,” they said in their report. Public Comment It is expected to be submitted to the FDA in 2022.

The association also said the voluntary system responds to consumer needs. “Facts Up Front” uses up to four icons on the front of packaging to highlight calories, saturated fat, sodium and added sugars per serving. Manufacturers can also include nutritional information for up to two “recommended nutrients,” such as potassium and dietary fiber. According to the Consumer Brands Association, hundreds of thousands of products have “Facts Up Front,” and as of 2021, it was listed on 207,000 foods and beverages, according to the most recent data available to the association.

“This is about giving consumers a quick, consistent and comprehensive understanding of the nutritional content of the products they buy so they can make informed decisions,” said Sarah Gallo, the association’s vice president of product policy.

Supporters of mandatory front-of-pack labeling disagree, arguing that the “Facts up Front” campaign is underused. In contrast, federally required nutrition facts labels on the back or side of packaging: Billions of products.

“Consumers can only have confidence in front-of-package labels if they appear throughout the entire food supply, not just on products from a few manufacturers who participate in voluntary programs,” said Eva Greenthal, senior policy scientist at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a food and health advocacy group that first petitioned the FDA for front-of-package labels in 2006.

She also said “Facts up Front” didn’t provide enough background information to be useful.

“Facts up Front doesn’t provide any additional tools to help consumers interpret that information,” she said. “You need words like ‘high in.'”

Courtney Gain, president and CEO of the Sugar Association, a trade group for the U.S. sugar industry, said her organization supports transparency but questions whether requiring front-of-package labeling would improve Americans’ diets.

“There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that this will make any difference,” she said.

But Greenthal and other advocates say there’s data from around the world to back it up. In Chile, which first introduced front-of-pack nutritional labeling in 2016, studies have shown that people are Healthier Consumer Purchasing Making healthier choices Product Improvement.

“I think it’s a classic anti-regulatory tactic of the food industry to dismiss the science that supports new policies that may be difficult to implement but are beneficial to society,” Greenthal said.

In its independent review of the scientific literature on front-of-package labeling, the FDA found that Conclusion It said the labels would “help consumers identify healthy foods” and “are likely to be useful to people with less nutritional knowledge and busy shoppers.”

The debate is centered on the percentage of Americans who are considered overweight or obese. AscendedDue to the effects of obesity About 42% of U.S. adultsOver 1 million Americans die from diet-related illnesses According to the FDA, the risk of death from cardiovascular disease, diabetes and certain cancers increases by more than 10 percent each year.

Zach Froehlich, an associate professor of history at Auburn University and author of “From Label to Plate: American Food Regulation in the Information Age,” said the statistics don’t mean that nutrition labels, which were mandated on the back and sides of food packages 30 years ago, are a failure.

“Every time a label has changed, the food industry has changed the formula of the food,” he says, “so even if you don’t read the label, the food is changing and that’s affecting you.”

Greenthal said there are many people who would benefit from more nutrition information on the front of packaging: busy parents rushing through supermarkets, people with low nutrition literacy and those with limited time and energy to devote to food choices.

“Policies like front-of-package labeling shouldn’t be implemented any sooner,” she said. “Diet-related chronic disease is one of the most significant issues facing our nation and a major drag on our public health.”