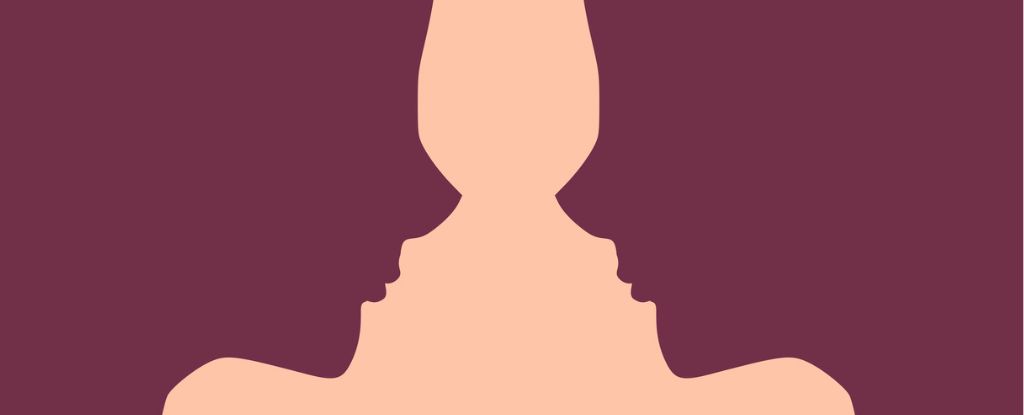

To transform reality into a mental landscape that occupies the mind, our brain performs numerous operations. Some are shortcuts. An assumption that becomes apparent the moment you try to make sense of the conflict presented in the optical illusion.

For people with autism, these shortcuts and mind manipulations work a little differently and can subtly affect how the brain constructs a picture of everyday life.

With this in mind, scientists turned to optical illusions To better understand neurodivergence.

A study of brain activity in 60 children, including 29 diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), found that differences in the way individuals process fantastical shapes suggest that autism is associated with specific processes in the brain. It suggests that it may reveal how it affects processing pathways.

This study made use of the classical style illusion popularized by Italian psychologists. Gaetano Canizza, which usually contains shapes such as simple lines or circles with sections removed. Empty space, arranged in a certain way, is arranged to represent her second shape of negative space.

To actually “see” different shapes, advanced processing operations in different areas of the brain combine stimuli to turn mere patterns of darkness into comprehensive images.

Depending on the information recruited, the stimulus can be interpreted as either form, but not both at once.

The entire process relies heavily on neurons sharing information rapidly, from the parts of the brain that determine perception, to the parts that receive visual data, package it, and put it back again.

Autism is defined as a neurological “spectrum disorder” because its characteristics are so diverse that each person exhibits different abilities, strengths, and challenges.

In general, however, research shows that many people with ASD process sensory information, such as sounds and sights, in non-standard ways.

Optical illusions are a good way to explore that neurodivergence.

For example, a 2018 study found that some individuals with ASD have trouble switching between seeing moving objects and seeing colors. In a general sense, their brains seemed to zoom in on details and ignore the big picture.

A similar trend was observed in this survey. With EEGs attached to the scalps of children sitting in chairs, focus on the central dot on the gray background of the screen in front of you and press the button when the dot changes from red to green. instructed.

The screen also displayed four contour images, randomly placed or aligned so that the negative space between them represented the shape.

By asking them to focus on the dots rather than the negative spaces, participants ‘passively’ observed the illusion in front of them and did not actively try to ‘solve’ it. .

Based on brain activity, children aged 7 to 17 years diagnosed with ASD showed delayed processing of the Kanitza illusion.

This does not necessarily mean that the participants were unable to discern the shapes formed by the outlining images, but it does suggest that the brain processed the illusion in a non-automatic manner.

“When we look at objects and pictures, our brains use processes that consider experience and contextual information to anticipate sensory input, deal with ambiguities, and fill in missing information.” I will explain Emily Knight, a neuroscientist at the University of Rochester.

“This indicates that these children may not be as predictive and fill in the missing visual information as their peers. We need to understand how it might be related to the atypical visual sensory behaviors we see in our spectrum.”

For example, another study A study by Knight published last year found that children with ASD struggled to process body language if they weren’t paying close attention.

When actively looking at the colors of moving dots on a screen, the EEG of people with ASD did not interpret the image as a walking human as intended.

“If their brains don’t process body movements very well, they can have trouble understanding other people, and they need to pay special attention to their body language to see it. Said Last year’s press release night.

“Knowing this can help usher in new ways to support people with autism.”

In the future, Knight hopes to continue working with larger cohorts that include people with a wider range of linguistic and cognitive abilities. Her ultimate goal is to find new and better ways to support children and adults on the autism spectrum.

This research Journal of Neuroscience.