Evidence also suggests that optimism is fundamentally equal across racial categories and is about the same in men and women. People who were optimists when they were young are more likely to remain optimists in old age.

But where does optimism come from? Dr. Elaine Fox, professor of psychology at the University of Adelaide, studies the neuroscience of optimism and pessimism. She frames these two attitudes of hers as manifestations of her two most basic urges of ours: seeking reward and avoiding danger.

These impulses, she explained, involve two major brain structures: the amygdala, which is associated with emotional responses such as fear and uncertainty, and our pleasure system. The nucleus accumbens is the nucleus accumbens. Both are ancient structures in common with many other animals. In humans, however, both structures are in constant conversation with the prefrontal cortex to moderate or reason with other parts of the brain.

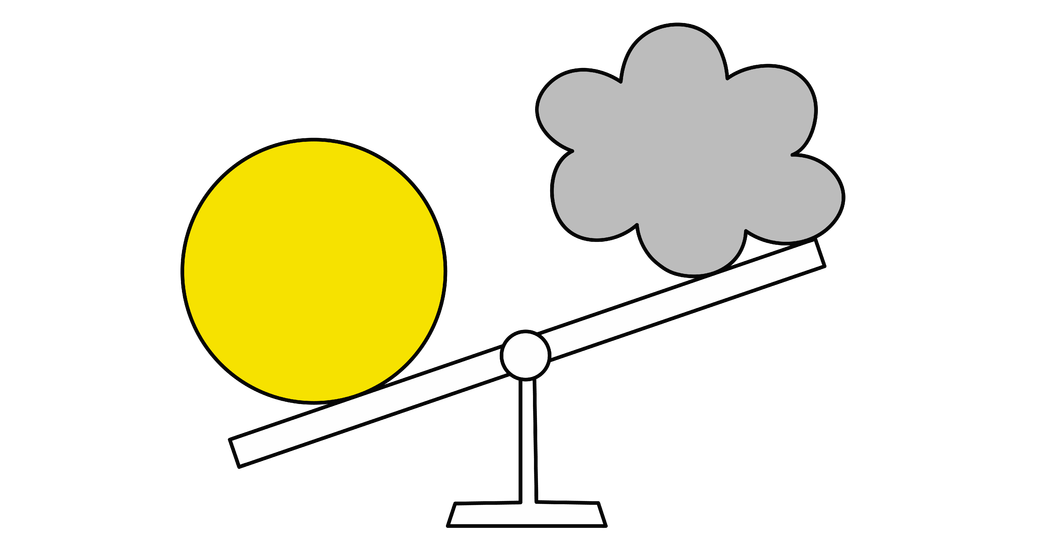

A standard analogy is accelerator and brake. In highly anxious people, the amygdala may be more active as an accelerator, while the prefrontal cortex is less likely to hit the brakes.In optimists, the nucleus accumbens may be more active. There is, said Dr. Fox, “but that control is also slightly less active.”

The pleasure system in the brain isn’t just about enjoyment and satisfaction, she explained. Dr. Fox argued that much of the success attributed to having an optimistic outlook is actually about persistence and adaptability. About doctrine she said.

Or, as Dr. Seligman puts it, “optimists try harder.” And that helps in all sorts of evolutionarily beneficial ways, including “sex and survival.”

We know that optimism is good for us on the whole, beyond the most basic evolutionary struggles. tend to be less likely to get