As I prepare to step down as a 54-year medical scientist and 38-year director at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a little self-reflection is inevitable. Looking back on my career, what stands out most is the remarkable evolution of the infectious disease field and the changing perception of the field’s importance and relevance by both academia and the general public.

I completed my residency training in internal medicine in 1968 and decided to join a three-year fellowship in infectious diseases and clinical immunology at NIAID. Unbeknownst to me, a young doctor, in the 1960s certain scholars and experts believed that with the advent of highly effective vaccines against many childhood diseases and the rise of antibiotics, the threat of infectious diseases, And perhaps along with it, it was rapidly disappearing to infectious disease specialists.1 Despite my passion for the field I was about to enter, had I known this skepticism about the future of this field, I might have reconsidered my choice of subspecialty. Diseases in other low- and middle-income countries were killing millions of people each year. Oblivious to this inherent contradiction, I happily pursued my clinical and research interests in host defense and infectious disease.

When I was away from the Fellowship for a few years, Dr. Robert Petersdorf, an icon in the field of infectious diseases, journal This suggests that infectious diseases as a subspecialty of internal medicine are being forgotten.2 In an article entitled “Physician’s Dilemma,” he wrote about the number of young doctors undergoing training in various internal medicine subspecialties: Professionals are not unless they spend time on each other’s culture. “

Of course, we all want to be part of a dynamic field.Are the selected fields static? Dr. Petersdorf Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine) voiced a common perspective that does not fully understand the truly dynamic nature of infectious diseases, particularly the potential for emerging and re-emerging infections. In the 1960s and 1970s, most physicians recognized the potential for a pandemic in light of the familiar precedent of the historic influenza pandemic of 1918 and the more recent influenza pandemics of 1957 and his 1968. was doing. A new infectious disease with the potential to dramatically impact society was still a purely hypothetical concept.

That all changed in the summer of 1981 with the confirmation of the first case of what would become known as AIDS. The global impact of this disease is staggering. Since the pandemic began, more than 84 million people have been infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and 40 million of them have died. In 2021 alone, 650,000 people died from her AIDS-related condition and 1.5 million were newly infected. Today, over 38 million people are living with HIV.

Although a safe and effective HIV vaccine has not yet been developed, scientific advances have led to highly effective antiretroviral drugs that have transformed HIV infection from an almost always fatal disease to a near normal life expectancy. transformed into a manageable chronic disease with Given the unequal access to these life-saving drugs globally, HIV/AIDS still takes a toll on morbidity and mortality 41 years after it was first recognized.

If there’s a silver lining to the emergence of HIV/AIDS, it’s that the disease has caused a surge of interest in infectious diseases among young people entering the medical field. In fact, with the advent of HIV/AIDS, Dr. Petersdorf was concerned that his 309 infectious disease trainees were needed. Honorably, a few years after his paper was published, Dr. Petersdorf was quick to admit that he had not fully realized the potential impact of emerging infectious diseases, and that young physicians were unaware of infectious diseases, She has become something of a cheerleader for pursuing a career, especially in HIV/AIDS practice. and research.

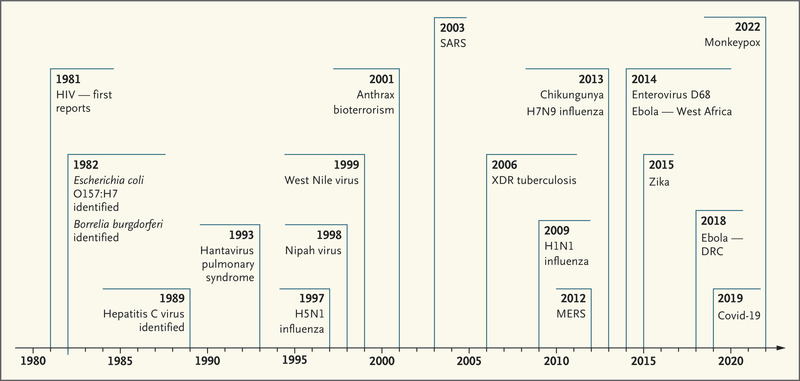

Selected milestones in the emergence of infectious diseases leading up to and during the author’s 40-year tenure as NIAID Director.

DRCs represent the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MERS Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, and widespread drug-resistant XDR.

Of course, the threat and reality of emerging infectious diseases was not limited to HIV/AIDS. During my tenure as Director of his NIAID, we faced the challenge of the emergence or re-emergence of numerous infectious diseases with varying degrees of local or global impact (see below). . Timeline). These included the first known human cases of H5N1 and H7N9 influenza. First Pandemic of the 21st Century with H1N1 Influenza (2009). Outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Africa. Zika fever in the Americas; Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) caused by another emergency coronavirus. And, of course, Covid-19 is his biggest wake-up call in more than a century to our vulnerability to emerging infectious disease outbreaks.

The global devastation caused by Covid-19 is truly historic and highlights the global lack of public health preparedness for an outbreak of this magnitude. However, one of the most successful components of the Covid-19 response has been the development of highly adaptable vaccines, such as mRNA (among others), made possible by years of investment in basic and applied research. The rapid development of the platform and the use of structural biology tools. Design of vaccine immunogens. The unprecedented speed with which a safe and highly effective Covid-19 vaccine has been developed, proven effective and distributed has saved millions of lives.3 Over the years, many subspecialties of medicine have greatly benefited from breathtaking technological advances. The same is true for the field of infectious diseases. This is especially true of the tools we currently have to address emerging infectious diseases, such as rapid, high-throughput sequencing of viral genomes. Development of rapid and highly specific multiplex diagnostics. Using structure-based immunogen design in combination with new platforms for vaccines.Four

The inevitable conclusion of my consideration of the evolution of the field of infectious diseases is that the experts of many years ago were wrong and the field is certainly not static. It’s really dynamic. In addition to the need to continue to improve our capacity to deal with established infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, among others, it is now clear that emerging infectious diseases represent a truly enduring challenge. One of my favorite experts, Yogi Berra, once said: Obviously, we can extend that axiom. For emerging infectious diseases, it’s never overAs infectious disease professionals, we must be relentlessly prepared and able to meet the constant challenges.