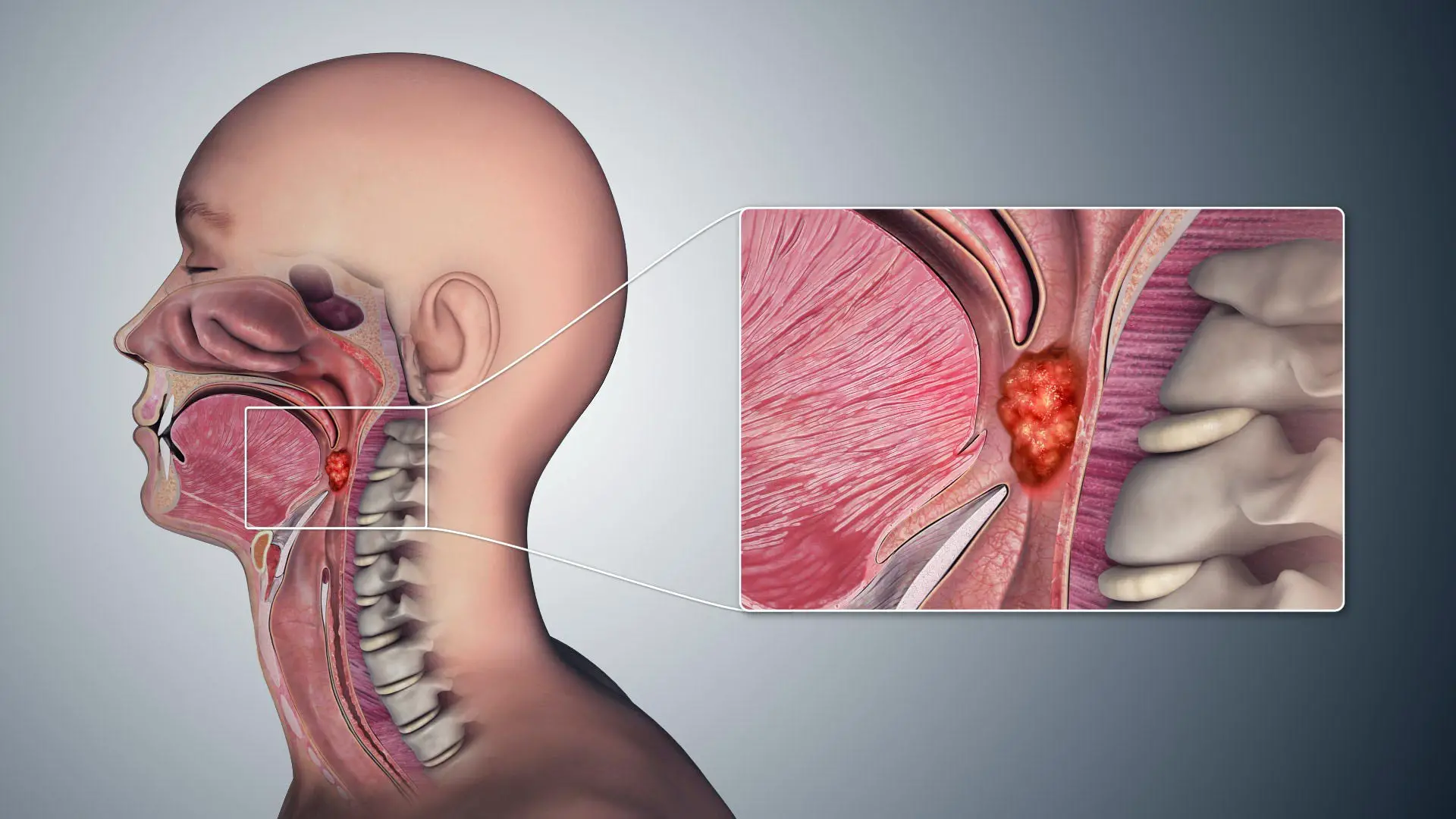

Over the past two decades, the incidence of a particular type of throat cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, has increased dramatically in the West, caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), in what some call an epidemic. This is an illustration of human papillomavirus.

The sexually transmitted disease human papillomavirus (HPV) is the primary cause of the surge in oropharyngeal cancer in the West over the past two decades. Despite the potential protective effect of HPV vaccination, challenges such as vaccine hesitation, low prevalence in certain regions, and behavioral trends can undermine its efficacy. Although gender-neutral vaccination policies have been introduced in several countries, there remain major obstacles to achieving comprehensive disease control.

Over the past 20 years, there has been a rapid rise in throat cancer in the West, as some call it. epidemicThis is due to a significant increase in a specific type of pharyngeal cancer called oropharyngeal cancer (the tonsils and the area in the back of the throat). The main cause of this cancer is human papillomavirus (HPV), which is also the leading cause of cervical cancer. Oropharyngeal cancer is now more common than cervical cancer in the US and UK.

HPV is a sexually transmitted disease. The main risk factor for oropharyngeal cancer is the number of lifetime sexual partners, especially oral sex.People who have six or more lifetime oral sex partners 8.5 times People who do not have oral sex are more likely to get oropharyngeal cancer.

Studies of behavioral trends show that oral sex very popular in some countriesIn a study my colleagues and I conducted in the UK on about 1,000 people who underwent tonsillectomy for reasons other than cancer, 80% of adults report having oral sex at some point in their lives.Fortunately, however, very few people develop oropharyngeal cancer. It’s not clear why.

A popular theory is that most of us have HPV and can be completely cleared. However, some people are unable to clear the infection due to defects in certain parts of their immune system. In those patients[{” attribute=””>virus is able to replicate continuously, and over time integrates at random positions into the host’s DNA, some of which can cause the host cells to become cancerous.

The oropharynx is middle section of the throat (pharynx). Scientific Animations/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

HPV vaccination of young girls has been implemented in many countries to prevent cervical cancer. There is now increasing, albeit as yet indirect evidence, that it may also be effective in preventing HPV infection in the mouth. There is also some evidence to suggest that boys are also protected by “herd immunity” in countries where there is high vaccine coverage in girls (over 85%). Taken together, this may hopefully lead in a few decades to the reduction of oropharyngeal cancer.

That is well and good from a public health point of view, but only if coverage among girls is high – over 85%, and only if one remains within the covered “herd.” It does not, however, guarantee protection at an individual level – and especially in this age of international travel – if, for example, someone has sex with someone from a country with low coverage. It certainly does not afford protection in countries where vaccine coverage of girls is low, for example, the US where only 54.3% of adolescents aged 13 to 15 years had received two or three HPV vaccination doses in 2020.

Boys should have the HPV vaccine too

This has led several countries, including the UK, Australia, and the US, to extend their national recommendations for HPV vaccination to include young boys – called a gender-neutral vaccination policy.

But having a universal vaccination policy does not guarantee coverage. There is a significant proportion of some populations who are opposed to HPV vaccination due to concerns about safety, necessity, or, less commonly, due to concerns about encouraging promiscuity.

Paradoxically, there is some evidence from population studies that, possibly in an effort to abstain from penetrative intercourse, young adults may practice oral sex instead, at least initially.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought its own challenges, too. First, reaching young people at schools was not possible for a period of time. Second, there has been an increasing trend in general vaccine hesitancy, or “anti-vax” attitudes, in many countries, which may also contribute to a reduction in vaccine uptake.

As always when dealing with populations and behavior, nothing is simple or straightforward.

Written by Hisham Mehanna, Professor, Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham.

This article was first published in The Conversation.![]()